Article of the Month -

August 2013

|

Innovative Approaches to Spatially Enabling Land Administration and

Management

Gary STRONG, Alexander ARONSOHN and Ben ELDER,

United Kingdom

1) This paper was presented

at the FIG Working Week, 6-10 May 2013 in Abuja, Nigeria. This paper

explores how, with only a small amount of investment, the development

and implementation of internationally agreed and recognised measurement

standards will support an improved market efficiency and providing a

wide range of beneficial tools to decision makers.

Key words: International Measurement Standards, Land Rights,

Real Estate, Land Administration and Management, RICS.

SUMMARY

This paper explores how, with only a small amount of investment, the

development and implementation of internationally agreed and recognised

measurement standards will support an improved market efficiency,

providing a wide range of beneficial tools to decision makers - from

benchmarking pricing of developments to the identification and valuation

of ownership collateral for the poorest in our societies to an increased

fiscal/tax raising potential from the establishment of a formalised land

and property market (fiscal cadastre).

A properly functioning, transparent and sustainable market in land,

property and construction is a fundamental building block of any

successful economy. The elements of such a market range from

registration of enforcement of land title, to accurate asset valuations

prepared in accordance with International Valuation Standards, to an

adequate supply of professionals working to common ethical principles.

One key missing ingredient that needs further attention at a global

level is a set of standards for the physical measurement of land and

buildings. RICS believes that the creation and establishment of

International Measurement Standards are an essential part of the process

to spatially enable land administration and management.

1. INTRODUCTION

The open market is the primary vehicle for the allocation of scarce

resources amongst competing needs in almost all economies in the World,

it is beholden on all civilised societies to recognise and take steps to

eliminate or reduce market inefficiencies where and when they occur.

“Market efficiency in economic terms occurs when the marginal cost

equals marginal utility in every market. Resources are inefficiently

allocated when marginal cost differs from marginal utility” (Lipsey &

Harbury, 1988, p. 102). This paper addresses one of the key areas of

market inefficiency, that of market knowledge. “The efficiency of

markets is reduced by imperfect knowledge” (Harvey & Jowsey, 2004,

p.29). Many mature economies have expended enormous energy and

investment on providing knowledge to markets in a variety of forms.

The World Bank estimates that “land and real estate assets comprise

50-70% of the national wealth of the world’s economies” (LARA, January

19, 2000). This being the case, even the smallest improvement in land

market efficiency will generate a significant beneficial effect to that

economy.

2. BACKGROUND

The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) objectives are

“to maintain and promote the usefulness of the profession for the public

advantage in the United Kingdom and in other parts of the world” and

“securing the optimal use of land and its associated resources to meet

social and economic needs” and “measuring and delineating the physical

features of the Earth” (RICS Thought Leadership, 2012, p. 7).

The RICS Foresight Land Use Futures Report (2010) commented on the

need for a better understanding of value in land use governance:

“How we value land, and the services it provides, is at the heart of

decisions on land use change. As priorities for land use and land

management shift (for example, to reflect long-term challenges

identified in this report) these need to reflected in how we govern land

use today.” The report goes on to call for “A more sophisticated

approach to valuing land…to be embedded into policy cycles and into the

governance mechanisms, including future incentives and regulation…The

appropriate concept of value” is seen as “a broad one, encompassing the

full range of ecosystem services, whether or not they are marketed” (p.

28). RICS has also explained (in the UK context) the often critical

issue of ‘land value’ and its calculation and its direct effects on

development viability in the 2012 best practice guidance ‘Financial

Viability in Planning’ (RICS, 2012, p. 23).

Peter Drucker (2009), a management consultant, famously once said;

“If you can't measure something, you can't manage it.” It equally

follows that if we use different measurement systems there is management

time taken in processing comparability and risk that the comparability

is flawed. Measurement is thus a fundamental ingredient of estimating a

value and a valuation is a fundamental means of decision-making through

the market mechanism. Equally it is for ‘what purpose/why’ we measure

that leads directly to ‘what’ we measure and then to the ‘how’ we

measure.

Measurement is one of the bases upon which decisions are made.

Measurement is not just about numbers; it is about the thinking and

analysis that the use of numbers enables. The scope of measurement is so

far reaching that it underpins not only all the work that we as

surveyors and land professionals do, but crosses many other fields and

specialisms. There are vast ranges of things that can be measured that

relate to the value and quantification of land and property and the list

below illustrates just a few:

- Floor/land Areas

- Volume

- Topography

- Productivity and Productivity Growth

- Agricultural Production

- Trade (Surplus and Deficits)

- Environment (Sustainability and Embodied Carbon)

- Poverty (GDP, PE ratios etc.)

- Market Volatility and price distortions

- Market Value (Measurement of Realisable Price)

- Natural Value

- Cost (both tangible and intangible)

- Embodied Carbon

- Profitability (ratios and absolute measures)

3. RESEARCH

RICS have undertaken primary and secondary research into the area of

real estate measurement and its global application. The research reveals

the absence of international standards for measurement of real estate,

furthermore measurement standards tend to vary on both a national and

regional basis. Certain elements of ‘measurement’ such as geodesy do

tend to be globally applicable and have a consistency in their academic

provision (http://www.iag-aig.org/) and the International Organization

for Standardization (www.iso.org) have created numerous internationally

agreed standards on ‘measurement’ instrumentation use, checking and

calibration (TC172) and on geographic information/geomatics (TC211). Yet

without internationally agreed measurement standards, it is not possible

to have valid and authentic cross border comparison, which would

facilitate both the evaluation and decision making process for land

administration and management.

4. PAPER

The Land Governance Assessment Framework (LGAF) (2012) comprises “a

set of detailed indicators to be rated on a scale of pre-coded

statements (from lack of good governance to good practice) based, where

possible, on existing information. These indicators are grouped within

five broad thematic areas that have been identified as major areas for

policy intervention in the land sector:

- Legal and institutional framework.

- Land use planning, management, and taxation.

- Management of public land.

- Public provision of land information.

- Dispute resolution and conflict management” (p. 2).

An agreed international measurement standard would help bring

transparency to each theme and would “allow follow-up measurement” and

“contribute to substantive harmonisation and coordination” (LGAF, 2012,

p. 21). In many countries, land rights could be strengthened through an

agreed international measurement standard that would allow more accurate

quantification to enable better coordinated spatial planning and land

management through increased land information quality that would make

service delivery more transparent.

In respect of the five broad areas currently being investigated as

part of the World Bank Agriculture and Rural Research Program,

productivity has to be measured by an internationally recognised

measurement standard before you can discuss raising productivity in

rural areas or analysing productivity growth in poor countries. Public

goods and externalities, which comprise the two sub categories of rural

infrastructure and community-based development, would require detailed

measurement to investigate the current situation and measure progress.

Finally, analysis of agriculture, trade and the environment, volatility,

and price distortions would require measurement, but to what measurement

standard? Would we need to be innovative or could we agree an existing

standard?

Innovative approaches can take many forms. They can involve, for

example, creating new solutions for old issues such as defining natural

value (a collaborative project currently being undertaken by RICS Land

Group) or looking at old issues in new ways. Trying to spatially enable

land administration and management without agreeing internationally

recognised measurement is a bit a like putting the cart before the horse

as each country/government would choose their measurement basis on the

results they could attain, be it a measurement of productivity, growth

or poverty.

The Land Government Assessment Framework is built around five main

areas for policy intervention: rights recognition and enforcement; land

use planning, land management, taxation, management of public land,

public provision of land information and dispute resolution and conflict

management. International Measurement Standards fit into all these

areas. For example, in order to have effective land use planning, land

management and taxation you first of all need to measure the land, map

the topography (as dictated in previous decades by ‘sale’ and

cartographic generalisation), and calculate the productivity in order to

have effective taxation. The same applies to management of public land

or the public provision of land information. Even rights recognition and

enforcement or dispute resolution would need some degree of

quantification and measurement in order to reach a successful

resolution. RICS is currently working with a number of organisations to

achieve international dispute resolution standards, which would also

assist in this process.

In respect of agricultural growth and productivity, which

investigates the role markets, risk and policy play in determining rural

livelihood strategies and the adoption of agricultural technologies and

the consequences of these outcomes for productivity and rural incomes,

measurement play a vital part. Yet impact and adaptation to climate

change, which focuses on the poverty impact of changing climate

volatility in Southern and Eastern Africa, would not be possible without

some agreed basis of International Measurement Standards. Moreover if we

consider distortions to agricultural incentives, true measurement of the

crops produced by the farmer and of the price deviations prevalent in

the local and international market, it would go some way towards

understanding and dealing with these very real issues and would also

help countries properly monetise their agricultural assets and grow

economically.

Land administration functions can be divided into four main

components: Juridical, regulatory, fiscal and information management.

Agreed principles based standards would aid the accurate establishment

of land rights and related security of tenure, which would allow the

regulatory side to operate more efficiently as accurate measurement is a

vital component of both fiscal and information management. The functions

of land administration comprising agencies responsible for surveying and

mapping, land registration and land valuation evidently include

measurement, but to what standard and in which jurisdiction?

Even though International Measurement Standards cannot be

underestimated as an essential building block to spatially enable land

administration and management it is also necessary to be cognisant of

the local measurement standards. In some cases, a dual standard of

measurement could be preferable with locals measuring according to both

local standards and units of measurement and to an internationally

agreed standard. The presence of dual systems can mirror that of a

‘formal’ and an ‘informal’ (but fully functioning market).

The FIG guide on standardisation from 2006 looks at ‘the benefits of

standards’, research undertaken by the Technical University of Dresden

and the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovations (available at

www.din.de/set/aktuelles/benefit.html) found that:

- The benefit to the German economy from standardisation amounts

to more than US$ 15 billion per year;

- Standards contribute more to economic growth than patents and

licences;

- Companies that participate actively in standards work have a

head start on their competitors in adapting to market demands and

new technologies;

- Transaction costs are lower when European and International

Standards are used;

- Research risks and development costs are reduced for companies

contributing to the standardisation process.

Further work in the UK in 2005 found that “13% of the UK’s economic

growth between 1948 and 2002 could be attributed to standards.” (DTI,

2005).

The UN-Habitat Global Land Tool Networks (GLTN) publication on ‘Handling

Land’ (2012), which looks at innovative tools for land governance and

secures tenure further defines land management and administration as

being sub divisible into the following four categories:

- “Land tenure: Securing and transferring rights in land and

natural resources.

- Land value: Valuation and taxation of land and properties.

- Land use: Planning and control of the use of land and natural

resources.

- Land development: Implementing utilities, infrastructure,

construction planning and schemes for renewal and change of existing

land use” (UN- Habitat, IIRR, GLTN, 2012, p.3).

All these categories have some form of measurement running through

their core. You cannot secure and transfer rights in land and natural

resources in a fair and equitable manner without an agreed method of

quantification. Measurement is a vital constituent of any valuation and

also forms the basis of a number of underlying assumptions in respect of

estimated rental values and anticipated growth. In respect of land use

planning and control, productivity cannot be measured without initially

measuring the size, topography and scope of land in the first place.

Finally development is underpinned by measurement at every stage from

pre-implementation to post construction, whether it is utilities,

infrastructure, renewal or change of use.

The GLTN handbook describes the following benefits from effective

land management and administration:

- Support of governance and the rule of law.

- Alleviation of poverty.

- Security of tenure.

- Support for formal land markets.

- Security for credit.

- Support for land and property taxation.

- Protection of state lands.

- Management of land disputes.

- Improvement of land use planning and implementation.

- Improvement of infrastructure for human settlements.

The GLTN see the responsibility of administering land as the task of

a range of “informal and formal institutions including government,

private and non-governments actors.” It goes on to state “unfortunately

conventional government land administration systems do not provide

security of tenure to the majority of the world’s people. They rely on

documents or computerised systems that record information…but most

people do not have legal documents for the land they use or occupy….and

limited land records and lack of information cause dysfunctionalities in

the management of urban and rural areas, from the household up to

national government level, which impairs the lives of billions of

people” (UN-Habitat, IIRR, GLTN, 2012, p. 4). The work of GLTN and

UN-Habitat is also directly connected to the land rights continuum (as

below) and embedded in the recently published Land Administration Domain

Model (LADM) international standard from FIG and ISO.

Figure 1: Land Administration Domain Model (LADM), Source ISO (2012)

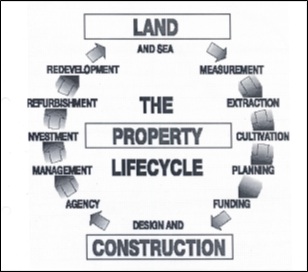

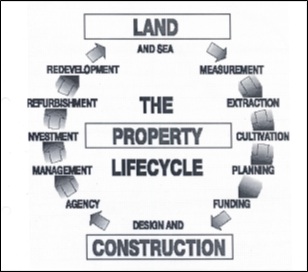

If we look at the Property Lifecycle chart below (Figure 2), it

becomes clear that measurement is a key aspect of this lifecycle. Not

only does land need measurement, but also accurate measurements are

required as part of every stage of the process even including eventual

redevelopment of the property, where measurement is once again

necessary. If we look at some less developed countries, large parcels of

land are not even measured, let alone registered and the creation of an

agreed international measurement standard would be the first step

towards enabling land administration and management. From an economic

perspective through land registration, there will be improved land and

asset values, security of tenure, as people will be able to prove and

pass on ownership. This in turn would help to stimulate local investment

and therefore the local economy. Further research into land registration

has been carried out on this topic in the RICS research paper on the

‘Valuation of Unregistered Land’ (2013).

Figure 2: Property Lifecycle, Source RICS (2012)

The development of International Measurement Standards is perhaps the

most vital land tool to take the first steps in contributing to poverty

reduction and sustainable development through promoting secure land and

property rights for all. As part of the development of these standards

one must recognise that “land issues are notoriously complicated and

they involve extensive vested interests. To design land tools that are

pro-poor, gender responsive and usable at scale requires inputs from

various disciplines, professions and stakeholder groups. The land tools

must be applied across different fields. That means the inputs from the

various specializations must be integrated, not merely co-existing in

‘silos. For this reason, land tools are best developed by

multi-disciplinary teams. This requires openness both to the content and

to new ways of working so that different views can be accommodated”

(UN-Habitat, IIRR, GLTN, 2012, p. 14).

There are currently an infinite number of competing international and

national measurement standards not only within the real estate industry,

but also across other fields and specialisms. These measurement

standards are often subject to national variance and regional

interpretation, although measurement underpins all valuation and

accounting.

The globally accepted standards for asset and liability valuation,

which includes all forms of land, property and real estate, are the

International Valuation Standards 2011 (IVS, 2011). IVS 2011 defines

basis of value as “a statement of the fundamental measurement

assumptions of a valuation” (IVS, 2011, p. 11), yet there is no

definition of measurement within these standards, even though some form

of measurement underpins not only valuations, but also the underlying

assumptions for these valuations. The measurements are subject to

national variation making it extremely difficult to have true comparison

of land valuations without knowing all the national bases and

deconstructing them in such a manner to make a common form of comparison

possible. In some countries, such as India, the situation is further

complicated by regional variations of measurement standards. This

situation could be resolved through the creation of international

measurement standards, which could initially work in tandem with the

existing national standards. In creating these standards it would be

possible to compare land values, productivity, performance and it could

be argued that these standards could act as a fundamental land tool or

cornerstone to spatially enabling land administration and management.

The RICS Valuation – Professional Standards (Red Book) are compliant

with IVS 2011 and also make several mentions of measurement. The Red

Book definition gives slightly more detail to the definition of basis of

value, which it defines as “a statement of the fundamental measurement

assumptions of a valuation, and for many common valuation purposes these

standards stipulate the basis (or bases) of value that is appropriate”

(RICS, 2012, p. 29), yet still falls silent on the issue of defining the

fundamental measurement assumptions, on which these valuations are

based. This is despite the fact that the Red Book also mentions the

measurements of the relevant land, the measurements of any such

buildings and the number of rooms in any such buildings and their

measurements. Though both the IVS and Red book are purposely set at a

high level and are prescriptive, providing the rules of valuation

without telling its practitioners how to value, a definition of these

fundamental principles of measurement is vital to bring further

transparency to the real estate industry. Unfortunately at an

international level this is still not possible, as no agreed

International Measurement Standard currently exists.

Both these valuation standards are compliant with International

Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) as valuations are required for

different accounting purposes in the preparation of the financial

reports or statements of companies and other entities. Examples of

different accounting purposes include measurement of the value of an

asset or liability for inclusion on the statement of financial position,

allocation of the purchase price of an acquired business, impairment

testing, lease classification and valuation inputs to the calculation of

depreciation charges in the profit and loss account. IFRS were developed

by the International Financial Reporting Standard Foundation working in

conjunction with the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB).

The goal of the IFRS Foundation and the IASB is to develop, in the

public interest, a single set of high quality, understandable,

enforceable and globally accepted financial reporting standards based

upon clearly articulated principles.

In pursuit of this goal, the IASB works in close cooperation with

stakeholders around the world, including investors, national

standard-setters, regulators, auditors, academics, and others who have

an interest in the development of high-quality global standards.

Progress towards this goal has been steady. All major economies have

established time lines to converge with or adopt IFRSs in the near

future. The international convergence efforts of the organisation are

also supported by the Group of 20 Leaders (G20) who, at their September

2009 meeting in Pittsburgh, US, called on international accounting

bodies to redouble their efforts to achieve this objective within the

context of their independent standard-setting process. In particular,

they asked the IASB and the US FASB to complete their convergence

project.

In order for Land Administration and Management to be truly global in

thinking and analysis, International Measurement Standards are required

for transparency and for more valid and authentic cross border

comparison and regulation. It is for this reason that we are advocating

the creation and promotion of a unified set of International Measurement

Standards, which can be agreed upon and supported by multiple

organisations and professional bodies, as is the case with the IFRS.

There is clear evidence that in many nations, the process of the

efficient and effective working of the property market is inhibited by

imperfections in the quality and transparency of property market

information. The imperfections are normally a consequence of the

technical attributes of the property market including transaction size,

heterogeneity, property rights and transaction costs. Through

development and adoption of truly international standards, we can

address market imperfections, and provide information based on the

highest ethical and professional standards that improve resource

allocation within the market for the public good.

In order to be meaningful, international principle-based standards

need to be developed by experts and be subject to broad and open

international consultation and stakeholder review in order to reassure

society and the international marketplace of the level of service they

can expect. International standards are drafted in such a way as to

allow professional bodies, and other appropriate organisations, to

assess conformity to the requirements.

How do we develop these International Measurement Standards and what

processes should we use? David Andre Singer’s book (2010) on Regulating

Standards looks at the way international standards were set for the

International Financial System. The book researches global regulation in

the three traditional pillars of finance; banking, securities and

insurance. Singer demonstrates that through “international regulatory

harmonisation regulators can impose sufficiently stringent regulations

on domestic financial institutions – and shore up stability while

relaxing the international competitive constraint that normally

prohibits such costly tightening”. He describes regulators as the “new

diplomats” due to their increasing visibility on the international scene

and says in some cases “the creation of international standards ties the

hands of a regulator by limiting its ability to adjust to changing

domestic or international circumstances” (Singer, 2010, pp. 2-3). In

reality, no regulator would accede to an international standard without

carefully considering its domestic environment. In fact Anne-Marie

Slaughter (2004), who is the University Professor of Politics and

International Affairs at Princeton University, makes the point that

“legislators lag far behind regulatory agencies in their international

activities and remain rather parochial in their outlook” (as cited in

Singer, 2010, p.7).

The International Financial System has much symmetry with the real

estate industry, apart from the direct connections that both “IVS 2001”

and the “Red Book” are IFRS compliant. Just as with land administration

and management, at the heart of any financial system is the problem of

asymmetric information, in which one party has more (and more accurate)

information about its own status than another party. Singer (2010)

argues that in respect of regulation the political legislature will

intervene in the financial sector in one of two circumstances: “First, a

bout of financial instability characterised by firm failures, asset

price volatility, or general crisis of confidence will create enormous

pressure to intervene. Second from the financial sector itself by

creating incentives for legislative intervention when regulations are

deemed too onerous compared to those in foreign jurisdictions” (p. 22).

In respect of real estate and measurement, there is a real danger of

political intervention on a national level unless professionals show the

ability to regulate themselves through the creation of an International

Measurement Standard. At present the way we measure property varies from

country to country. This leads to significant discrepancies in reporting

in an industry that, these days, is defined more by global

financial-return than location.

Singer (2010) argues that there are three main types of

harmonisation. “The first regulatory convergence is the organic process

but which countries modify their regulations based on the policies of

other countries or simply converge on a common set of rules

inadvertently. The second type of harmonisation is called core

harmonisation and is the process where a small group of advanced

industrialised countries agree, through overt negotiation, to harmonize

their regulation. The result of successful core harmonisation is an

international standard. The creation of an international standard gives

rise to the third type of harmonisation, peripheral harmonisation, in

which countries outside the core group of industrialized countries

choose whether to accede to the standard or to maintain divergent

standards” ( p. 122).

Although in accord with the three main types of harmonisation

mentioned here, a fourth type of harmonisation that is becoming

increasingly prevalent today is known as forced harmonisation. If we

look at the recent major global recession, we could argue that it was

characterised by various systemic imbalances, which sparked the outbreak

of the financial crisis of 2007–2008. We could highlight a number of

markets where these systematic imbalances were present such as the sub

prime mortgage crisis with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The US Securities

and Exchange Commission are a federal agency, they hold primary

responsibility for enforcing the federal securities laws and regulating

the securities industry. The nation's stock and options exchanges, and

other electronic securities markets in the United States, responded to

these crises by enforcing further regulation within these markets.

Paul Beswick, who is the Deputy Chief Accountant, US Securities and

Exchange Commission made the following comments in his speech on

December 5, 2011 in respect of real estate valuation “Risks created by

the differences in valuation credentials that exist today range from the

seemingly innocuous concerns of market confusion and an identity void

for the profession to the more overt concerns of objectivity of the

valuator and analytical inconsistency.” (Beswick, 2011, p. 4). His

speech highlights two main issues. The first is if the real estate and

those dealing with the real estate do not take the first steps to

regulate themselves, then external regulation will come through other

bodies, who may not fully comprehend the complexities and checks and

balances that lie within the real estate industry and the industry would

lose some of its right to self determination and regulation. The second

main and perhaps more important issue is that market confusion and

analytical inconsistencies are currently embedded within the real estate

industry. This is true of all specialisms and equally applicable to land

administration and management.

Another way of solving market confusion and analytical

inconsistencies within both the real estate industry in general and more

specifically within land administration and management would be the

creation of International Measurement Standards. Measurement relates to

all aspects of the real estate industry and in the majority of cases is

the vital first block on which the foundations are built, whether it be

land tenure, land use, land value or land development. “If there were no

international trade and no international communications, international

standards would hardly be necessary! But international trade and

communications are imperatives, especially in modern times.” (Hunter,

2009, p. 75).

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and

International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) explore in their

Directive 2 “Rules for the structure and drafting of International

Standards.” This directive defines a standard as a “document,

established by consensus and approved by a recognized body, that

provides, for common and repeated use, rules, guidelines or

characteristics for activities or their results, aimed at the

achievement of the optimum degree of order in a given context” and notes

that “Standards should be based on the consolidated results of science,

technology and experience, and aimed at the promotion of optimum

community benefits.” It further defines an International Standard as “a

standard that is adopted by an international standardizing/standards

organization and made available to the public.” (ISO/IEC Directives,

Part 2, 2011, p. 8). The document also looks at a “technical

specification”, which it defines as a “document published for which

there is the future possibility of agreement on an International

Standard, but for which at present:

- The required support for approval as an International Standard

cannot be obtained.

- There is doubt on whether consensus has been achieved.

- The subject matter is still under technical development.

- There is another reason precluding immediate publication as an

International Standard” (ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2, 2011, p. 9).

Hunter (2009) in his book “Standards, Conformity Assessment, and

Accreditation For Engineers” examines standards development and says

that there are three primary processes for developing standards:

- Classical Methods (also called traditional or formal methods).

- Consortia and similar methods.

- Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) methods.

He states, “these methods should not be considered to be mutually

exclusive. Many important standards development projects involve more

than one of these approaches” (Hunter, 2009, p. 51).

RICS have explored the processes for developing standards and

consider classical methods for standards adoption too laborious and

prescriptive at times, especially when there is an immediate need for

measurement standards in many parts of the developing world. RICS is in

the process of establishing a quasi coalition for the creation of

international measurement standards - to achieve a goal that none of the

individual organisations can achieve on its own. Standard setting

consortia, apart from bodies such as IEC and ISO (founded in 1906 and

1947 respectively) are a recent development and the “motivation for the

establishment of such consortia and the relatively long time it

frequently takes for standard development organisations to develop a

standard. Consortia are frequently able to set a standard in a

relatively short time” (Hunter, 2009, pp. 59-60). A good example of this

type of consortia is the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC

http://www.opengeospatial.org/standards/is).

We need to ensure the international standard that we create is

globally relevant and beneficial. The World Trade Organisation (WTO)

looked at this issue in the committee on Technical Barriers to Trade

Document commented on this in Part IX, paragraph D, Effectiveness and

Relevance, which states: “In order to serve the interests of the WTO

membership in facilitating international trade and preventing

unnecessary trade barriers, international standards need to be relevant

and to effectively respond to regulatory and market needs, as well as

scientific and technological developments in various countries. They

should not distort the innovation and technological developments in

various countries. They should not distort the global market, have

adverse effects on fair competition, or stifle innovation and

technological development. In addition they should not give preference

to the characteristics or requirements of specific countries or regions

when different needs or interests exist in other countries or regions.

Whenever possible international standards should be performance based

rather than based on design or specific characteristics.” (WTO, 2002, p.

26).

The creation of a global consortium headed by organisations such as

the World Bank would help ensure that the resulting International

Measurement Standard would be globally relevant and facilitate

international national trade while preventing unnecessary trade

barriers. It would also ensure that the resulting standards are not

partisan to any particular country or organisation and that they are

relevant and effectively respond to market needs without distorting the

global market or adversely effecting fair competition. Finally and most

important of all it would ensure that the resultant standards would

serve the global public interest. The International Bank for

Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and the International Development

Association (IDA) both form part of the larger body known as the World

Bank Group. The IBRD aims to reduce poverty in middle-income and

creditworthy poorer countries, while IDA focuses exclusively on the

world’s poorest countries. Both these aims can be furthered through the

creation of an International Measurement Standard that would ensure fair

and effective global land registration that would encourage increased

international investment. Accordingly, an effective land management and

registration system cannot occur without an agreed system for

quantification.

In order to create these standards though it is necessary to have a

look at the stages for international standards development. The WTO-ISO

developed a stage code system to enable the stages of development of an

international standard to be identified. The five stages of development

were mandated as follows:

Stage 1: The stage at which the decision to develop a standard has

been made.

Stage 2: The stage at which technical work has begun but for which the

period of comments has not yet started.

Stage 3. The stage at which the comment period has started but has not

yet been completed.

Stage 4: The stage at which the period for the submission of comments

has been completed, but the standard has not yet been adopted.

Stage 5: The stage at which the standard has been adopted.

In some cases it may also be possible to adopt a fast track

procedure. If a document with a certain degree of maturity is available

at the start of a standardisation project, for example a standard

developed by another organization, it is possible to omit certain

stages. In the so-called ‘Fast-track procedure’, a document is submitted

directly for approval as a draft International Standard or, if the

document has been developed by an international standardizing body

recognised by the consortium, as a final draft International Standard

without passing through the previous stages.

Subsequently the ISO have their international standards developed by

ISO technical committees (TC) and subcommittees (SC) by the following

six-step process. Those most commonly related to surveying and

measurement activities are within TC211, TC172, and TC59.

- Proposal stage

- Preparatory stage

- Committee stage

- Enquiry stage

- Approval stage

- Publication stage

Once the final draft International Standard has been approved, only

minor editorial changes, if and where necessary, are introduced into the

final text. The final text is sent to the ISO Central Secretariat, which

publishes the International Standard. In some cases it may also be

possible to adopt a fast track procedure. If a document with a certain

degree of maturity is available at the start of a standardisation

project, for example a standard developed by another organization, it is

possible to omit certain stages.

In respect of an International Measurement Standard, RICS is

currently at Stage 1 or the proposal stage. RICS has identified a number

of stakeholder coalition partners from all the world regions, who have

identified the global need for international standards and who are

having an initial stakeholder meeting to discuss and agree the processes

for the creation of an International Measurement Standard. Initially the

RICS are focussing on international property measurement standards

comprising Land, Property and Construction. It is hoped that once the

impetus is created through the establishment of these standards the

consortium will widen the remit of measurement and also look at

measurement of Productivity and Productivity Growth, Agricultural

Production, Trade (Surplus and Deficits), Environment (Sustainability),

Poverty (GDP, PE ratios etc.), Embodied Carbon and Profitability (ratios

and absolute measures). These forms of measurement will also assist in

spatially enabling land administration and management, but in order to

apply these international standards and as effectively as possible it is

necessary first of all to focus on one aspect of measurement.

RICS has decided that in order to develop International Measurement

Standards, it should initially look at International Property

Measurement Standards with Property being defined as anything pertaining

to Land, Property and Construction. RICS research has shown that with

the exception of organisations such as the World Bank, there is no

organisation or professional body that deals with measurement in all its

form and even within the Property/Real Estate Industry there is limited

agreement within, let alone across disciplines.

An example of this is a preliminary study, which RICS carried out in

May 2010, focussing on the office market. The aim of the study apart

from serving the public interest was stated as twofold:

- In addition to current codes or standards used nationally (or

regionally), a standard international code of measurement would be a

tool for the consistent reporting of building areas (commercial

space) by surveyors and companies that work across borders and

market practices.

- For those working in emerging markets or countries (regions)

here there is currently no code or standard in use; an international

code of measurement may form the basis of, and help to establish,

some standard form of measurement standard.

The study looked at the RICS Code of Measuring Practice, Draft

European Measuring Practice, UGEB Code and BACS Code in Belgium, The

standard for calculating the Rentable Value of Commercial Premises (GIF)

in Germany, The Code of Measuring Practice for Spain, NEN 258 in the

Netherlands, Method Of Measurement by the Property Council of Australia,

the USA Unified Approach for Measuring Office Space: For use in Facility

and Property Management, The USA BOMA Office Space Standard 2010,

Measuring Practice Guidance Notes for Ireland, Code of Measuring

Practice or Hong Kong and the Code of Measuring Practice for the United

Arab Emirates. RICS also produces numerous other measurement orientated

best practice guidance documents such as ‘Surveys of land, buildings and

utilities at scales of 1:500 and larger 2nd Ed 1997’, ‘Use of GNSS in

surveying and mapping 2010 2nd Ed’ and ‘Vertical aerial photography and

derived digital imagery 5th Ed 2010’.

In examining these existing standards, a chart was made of all the

similarities in respect of office measurement to see if any common

ground could be found. Though there was some common ground between the

different codes, it proved highly difficult to reach an agreement, as

each country was convinced of the merits of its own code and felt that

other organisations or professional bodies should adopt its standards

rather than adopting other organisations’ standards or creating new

standards. In analysing the difficulties we had in respect of this

project it was noted that one of the main issues was that we had in

establishing an agreed standard is that we started from the micro level

(i.e. the actual standards) and tried to find a point of resolution. A

better process, as shown by both psychological and mediation theories,

is to start from a point of agreement. Discussing and agreeing the

importance of measurement and exploring the fundamental principles by

which all forms of measurement must abide could initiate the process.

RICS has carried out multi-disciplinary research to examine the

fundamental principles that lie behind a number of specialisms, all of

which use some form of measurement. The research looked at the following

disciplines: administration and support service activities, archaeology,

construction, education, engineering, financial and insurance

activities, home health and social work activities, land geomatics,

manufacturing, mining and quarrying, physics, professional scientific

and technical activities, water supply, transportation and storage and

waste management and remediation activities. The majority of these

disciplines had numerous measurement and other standards within their

disciplines but no real fundamental principles that lay behind them. In

addition as with real estate there were a number of competing

professional bodies, on both a regional and national basis, each with

their own standards. The exceptions to these were construction,

engineering and physics.

In respect of construction, as with other disciplines, measurement

seems to be largely based on national lines with wide variations in

terms of what is measured and how this is done. In respect of housing

measurement in the USA, the following principle exists in respect of the

measurement of residential square footage in single family dwellings:

“In the calculation, the objective must be to measure accurately,

calculate competently, and identify the improvements in a manner that is

not misleading and describes and/or facilitates an understanding of the

property.” (Hampton Thomas, 2008, p. 12) In the case of engineering the

value of consistent and valid measurement of such properties has led to

the development of standard test methods, i.e., “standards”. Standards

specify measurement details such as specimen design, test apparatus and

calibration, test procedures, data reporting, limits of applicability,

and uncertainty. The standards are usually up-dated with significant

contribution and review by the technical community concerned.

International standards are generally developed through the cooperative

efforts of national or regional standards organisations and reflect the

methods developed for those bodies’ standards.

In order to find true fundamental principles it is necessary to look

at the field of physics, which has the following six guiding principles

developed by the National Physical Laboratory, which one should follow

if you want good measurement results:

- Make the right measurements.

- Use the right measurement tools.

- Use the right measurement procedures.

- Use the right people to do the measurement.

- Review your measurement regularly.

- Demonstrate how consistent the measurement is.

The RICS has analysed these fundamental principles and drafted some

preliminary fundamental principles that we believe would be applicable

to all forms of measurement. These principles comprise high-level

standards that we believe would be acceptable to all professional bodies

and are beyond national boundaries and statutory legislation. In effect

they are fundamental principles that lie behind all measurement. These

fundamental principles, which lie behind every measurement, would need

to be discussed and agreed with other organisations, but an example of

these is shown below:

- The item must be capable of being measured.

- There must be a unit of measurement.

- The measurement must be quantifiable.

- The measurement must be repeatable.

- The measurement must be comparable against other similar forms

of measurement.

- The measurement must be objectively verified.

- The basis of measurement must be agreed.

- The standard or unit of measurement must be agreed.

- The measurement must be transparent.

- The measurement tolerance must be agreed.

Though International Measurement Standards that deal with all forms

of measurement as outlined above do not currently exist, it would be

possible to create both these standards and agree the fundamental

principles of measurement by working collaboratively with the World Bank

and other international and national, Governmental and Non-Governmental

bodies and professional bodies and organisations. In order to achieve

International Measurement Standards, RICS is gathering the leading

international stakeholders in measurement (of all asset classes) at a

round-table discussion to address existing fragmentation and assist in

the resolution of this industry wide issue. The agreement of these

standards would play a vital role in spatially enabling land

administration and management.

Initially RICS is focussing on broad based real estate measurement

standards, which are applicable to all asset classes. Examples of these

types of real estate measurement standards are site area/land area/plot

area/development area, all of which are vital to effective land

registration and administration. We can then continue to work

collaboratively with other stakeholders in order to agree further

International Measurement Standards by updating existing standards,

negotiating agreed standards, adopting existing standards and agreeing

high-level standards with other professional bodies. This will not mean

the disappearance of national standards as in many cases national

standards need to exist due to local government legislation and it may

not be possible to agree an international standard. In these cases it

would be possible to agree a dual reporting system, where the countries

report their measurements according to both an agreed international and

the appropriate national measurement standard.

5. CONCLUSION

RICS believes the creation of International Measurement Standards

would be a vital tool for all five broad areas currently being

investigated by the World Bank Agriculture and Rural Research Program.

Raising productivity in rural areas, productivity growth in poor

countries, public goods and externalities, agriculture trade and the

environment and poverty and price distortions all require measurement,

but to which standard? If an agreed International Measurement Standards

is not used, the temptation would be to pick the measurement standards

that gave the best results and the best impression of the government and

its policies. If this where the case any reported figures would be

discoloured at best.

In addition as illustrated four of the five main areas for policy

intervention within the Land Government Assessment Frameworks (i.e.

rights recognition and enforcement, land use planning, land management

and taxation, management of public land and provision of public land)

are all related to measurement in some way and would benefit from an

agreed International Measurement Standard. In fact it could be argued

that measurement of land would be a vital and fundamental component of

the land rights recognition process.

Moreover the five broad thematic areas, that have been identified and

discussed in this paper as major areas for policy intervention, would

substantially benefit from an agreed International Measurement Standard.

This would help bring transparency to each thematic and “would allow

follow-up measurement” and contribute to substantive harmonisation and

coordination” (LGAF, 2012, p. 21).

As already mentioned Global Land Tool Networks (GLTN) research, which

looks at innovative tools of land management and secure tenure, divides

land management and administration into the following four categories:

Land tenure, land value, land use and land development. All these

categories have measurement running through their core, yet there is no

agreed International Measurement Standard which focuses on the why, what

and how of measurement that would allow cross border comparison.

Furthermore in many countries there is not even a national measurement

standard, which would allow comparison between states. The RICS Property

Lifecycle Diagram (Figure 2) contained within this paper further

illustrates this point. In fact it could be argued that the development

of International Measurement Standards is perhaps the most vital land

tool to take the first steps in contributing to poverty reduction and

sustainable development through promoting secure land and property

rights for all via accurate quantification.

In our examination of the relationship between International

Financial Reporting Standards and International Valuation Standards (IVS

2011) and the RICS Valuation – Professional Standards (The Red Book) we

have noted that though these standards define the basis of value as “a

statement of the fundamental measurement assumptions of a valuation”

(IVS, 2011, p. 11), none of these standards defines either measurement

or the basis of this measurement. There is clearly a need for an

International Measurement Standard to spatially enable land

administration and management. Through exploring the methodology for

creating international standards and looking at examples of standard

setting within the accounting, engineering and financial regulations

industry RICS has concluded that the best process for establishing an

International Measurement Standard is via the creation of a consortia or

coalition partnership.

Our preliminary research into office measurement standards illustrate

the variety of measurement standards that are currently available within

each specialist niche of the real estate industry and the difficulties

that this can create in respect of agreeing an international standard.

Our research has led us to conclude that in order to create an

International Measurement Standard, which will spatially enable land

administration and management we need to agree the fundamental

principles on which all measurements are based, rather than getting

embroiled in each countries or organisations particular standard. RICS

has therefore carried out a cross specialism research on the fundamental

principles that lie behind measurement and has discovered that at this

point in time the most relevant fundamental principles that could be

applied to measurement come from the field of physics. We have therefore

analysed these principles of measurement and drafted a set of

fundamental principles, which could apply to land administration,

management and the real estate industry as a whole.

In conclusion, the creation of internationally recognised measurement

standards would help bring transparency to the field of land governance

and would be a key stepping stone for the research currently being

carried out by non governmental organisations such as the World Bank

Agriculture and Rural Research Program, which examines the following

areas; raising productivity in rural areas, productivity growth in poor

countries, public goods and externalities, agriculture, trade and the

environment and poverty, volatility, and price distortions. We would

therefore like to invite FIG and other organisations attending the FIG

working week 2013 to collaborate on international measurement standards

as part of an innovative approach towards spatially enabling land

administration and management.

REFERENCES

- Beswick, P. A. (2012). Prepared remarks for the 2011 AICPA

national conference on current SEC and PCAOB developments. USA:

Securities and Exchange Commission.

http://www.sec.gov/news/speech/2011/spch120511pab.htm

- CIMA. (2005). International financial reporting standards in

depth: Volume 1 Theory and Practice. Great Britain: Elsevier and

CIMA.

- CIMA. (2005). International financial reporting standards in

depth: Volume 2 Solutions. Great Britain: Elsevier and CIMA.

- Deininger, K., Selod, H. and Burns, A. (2012) The Land

Governance Assessment Framework: Identifying and monitoring good

practice in the land sector. Washington DC, USA: The World Bank.

- DTI. (2005). The Empirical Economics of Standards.

www.dti.gov.uk/iese/The_Empirical_Economics_of_Standards.pdf.

- Drucker, P. (2009). “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage

it.”.

http://blog.marketculture.com/2009/03/20/if-you-cant-measure-it-you-cant-manage-it-peter-drucker/.

- Government Office for Science. (2010). Foresight land use

futures project. London, Great Britain: Government Office for

Science.

- Harvey, J. & Jowsey, E. (2004). Urban Land economics 6th

edition. Great Britain: Palgrave Macmillan Limited.

- Hampton Thomas, D. (2008). American Measurement Standard. USA:

Measure Man.

- Hunter, R. D. (2009). Standards, Conformity, Assessment and

Accreditation for Engineers. New York, USA: Taylor & Francis Group.

- International Valuation Standards Council. (2011). International

valuation standards 2011. Norwich, Great Britain: Page Bros.

- ISO/IEC. (2011). ISO/IEC Directives Part 2: Rules for the

structure and drafting of International Standards. Geneva,

Switzerland: ISO.

- Lipsey, R. & Harbury, C. (1988). Principles of Economics. Great

Britain: Oxford University Press.

- RICS Thought Leadership. (2012). Challenges for international

professional practice: From market value to natural value. Great

Britain: Direct Approach.

- RICS. (2012). RICS valuation: Professional standards. Great

Britain: Page Bros.

- RICS Professional Guidance. (2012). Financial viability in

planning. Great Britain: Page Bros.

- RICS. (2007) Surveying sustainability: A short guide for the

property professional. Great Britain: AccessPlus.

- Singer, D. A. (2010). Regulating capital: Setting Standards for

the International Financial System. USA: Cornell University Press.

- UNHabitat, IIRR, GLTN. (2012). Handling Land: Innovative tools

for land governance and secure tenure. Nairobi, Kenya: Publishing

Services Section.

- UN Habitat, GLTN (2012). Land and Property Tax, a policy guide,

Nairobi, Kenya: Publishing Services Section

- World Trade Organisation. (2002). The Committee on Technical

Barriers to Trade Document G/TBT/1/Rev.8: Decisions and

Recommendation Adopted by the Committee since 1 January 1995.

http://www.astm.org/GLOBAL/images/wto.pdf

FIGURES

- ISO. (2012). Land Administration Domain Model (LADM).

Switzerland, Geneva: ISO Publishing.

- RICS. (2012). Sustainability and the RICS Property Lifecycle.

Great Britain: Page Bros.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Gary Strong BSc(Hons) FRICS FCIArb FBEng FCILA FUEDI-ELAE

Qualified as a Chartered Building Surveyor, and practicising as a

surveyor and arbitrator for 29 years. Qualified as both an arbitrator

and loss adjuster additionally. Highlight of a varied career was the

landmark House of Lords case of Delaware Mansions (Flecksun Ltd) –v-

City of Westminster.

Gary commenced his interest in surveying at the age of 14 when he

undertook an O-level in surveying, subsequently pursuing this interest

in surveying with a building surveying degree at University of Reading.

On graduation in 1980, he went to work for the PSA (DOE) where he

qualified as well as gaining experience on MOD and Civil Estate

buildings.

Moving to London in 1984, he became a Partner in Filby McCann &

Bracken a chartered building surveying practice and then moved to

Crawford & Co to become Surveying Director of a large international

company with over 10,000 staff.

For 10 years he was Subsidence & Surveying Services Director at GAB

Robins a large multi-disciplinary international organisation prior to

joining RICS in 2007 as Director of Practice Standards & Technical

Guidance heading up Professional Groups & Forums.

Gary is a member of the Senior Management Group at RICS and is a

regular spokesman & conference speaker on built environment issues.

CONTACTS

Gary Strong

Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors

Parliament Square

London SW1P 3AD

UNITED KINGDOM

Tel. + 44 (0)20 7695 1522

Fax + 44 (0)20 7334 3712

Email: [email protected]

Web site: www.rics.org

|