Katerina ATHANASIOU, Efi DIMOPOULOU, Christos

KASTRISIOS and Lysandros TSOULOS, Greece

The interests, responsibilities and opportunities of states to

provide infrastructure and resource management are not limited to their

land territory but extend to marine areas as well. So far, although the

theoretical structure of a Marine Administration System (MAS) is based

on the management needs of the various countries, the marine terms have

not been clearly defined. In order to define a MAS that meets the

spatial marine requirements, the specific characteristics of the marine

environment have to be identified and integrated in a management system.

To explicitly define MAS, certain issues need to be addressed such as:

the types of interests that exist in marine environment, the best way to

capture and register those interests, laws defining these interests, and

their hierarchical classification, as well as how this classification

can be used to produce the principles for the implementation of MSP. In

addition, the registration of laws in a MAS that could automatically

define the constraints of the emerging Rights, Restrictions and

Responsibilities (RRRs) should be addressed, along with property/ tenure

object definition. Further questions need to be answered e.g., what is

the basic reference unit and how can this be defined, deliminated and

demarcated, capturing the 3D presence of marine parcel and is the

traditional definition of a cadastral parcel applicable in a marine zone

defined by United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (Hereinafter:

UNCLOS) (United Nations, 1982) and how could the fourth dimensional

nature of marine RRRs be included. Addressing these questions

constitutes the basis upon which a MAS can be built. However, the most

crucial question is how the international standards and practices of

land administration domain can be used for managing the marine

environment. The aim of this paper is to examine the above questions, to

probe the ways the legislation can be included into a MAS and to present

how RRRs relating to marine space may be defined and organized, in order

to develop a MAS based on international standards by means of not only

trading in marine interests, but rather facilitating the management of

activities related to resources.

1. INTRODUCTION

Over the last two decades, countries with extensive coastlines and

confined marine space, where they exercise sovereignty and powers, have

dealt with the concept of MAS. Among others Australia, Canada, the

Netherlands and the United States have developed systems for the

administration of marine interests and the sustainable management of

marine resources (Athanasiou et al, 2015). Their efforts are at a

development stage, based on practices adopted in the fields of Marine

Cadastre (MC), Marine Spatial Data Infrastructure (MSDI), Marine Spatial

Planning (MSP).

Many definitions have been given to MC, as Nichols et al (2006)

extensively described. It can be broadly defined as “an information

system that records, manages and visualizes the interests and the

spatial (boundaries) and non-spatial data (descriptive information about

laws, stakeholders, natural resources) related to them”. MSDI is

fundamental to the way marine information is developed and share for

competent marine administration. MSP is a planning frame for balancing

the rival human activities and managing their effects in the marine

environment.

Research has been carried out concerning the correlation between

these concepts and the way they interrelate. MC and MSDI relationship:

MC is defined as a management tool, which can be added as a data layer

in a marine SDI, allowing them to be more effectively identified,

administered and accessed (Rajabifard et al, 2005; Rajabifard et al,

2006; Strain et al, 2006; Widodo et al, 2002; Widodo, 2003; Widodo,

2004). Furthermore regarding the relation of MC and MSP, according to

Arvanitis (2016), there is a two-way relationship between MSP and MC:

“Both of them function independently. However, MSP is designed and

implemented safely and at a lower cost if it utilizes data from MC and

MC will register and control the different rights and licenses in marine

areas based on ecological environment when defined zoning from MSP

exist.” According to De Latte, 2015 “A MC is also different to a MSP as

referred to in the directive 2014/89; a MSP is intended to regulate the

use of the marine area/areas it covers; a MC is intended to describe and

delimit distinct MC parcels and to indicate all relevant public and

private rights, restrictions (including inter alia the restrictions

resulting from MSP) and charges on those parcels.”

MASs show the different perspectives of the various jurisdictions,

while the tools developed for the management of marine environment show

the increasing institutional and research interest on this topic.

However, there is a lack of a common standard regarding the management

of marine Rights, Restrictions and Responsibilities (RRRs) and their

spatial extent. Current research focuses on the development of a MC data

model that would serve as the basis of a MAS, taking into account

existing standards. Concerning modeling aspects, 83 Katerina Athanasiou,

Efi Dimopoulou, Christos Kastrisios and Lysandros Tsoulos Management of

Marine Rights, Restrictions and Responsibilities according to

International Standards 5th International FIG 3D Cadastre Workshop 18-20

October 2016, Athens, Greece Ng’ang’a et al (2004) describe a marine

property rights data model, Duncan and Rahman (2013) advocate the

integration of marine blocks with land volumes, Griffith-Charles and

Sutherland (2014) examine the creation of a 3D Land Administration

Domain Model (LADM) compliant MC in Trinidad and Tobago, while

Athanasiou, 2014; Athanasiou et al, 2015 deal with the conceptual

classification of the marine entities and relationships and explore the

adaptation of LADM to marine environment. Furthermore, in several

countries the management of marine cadastral units is included in the

LADM implementation. Among the existing standards that could relate to

marine environment special reference can be made to:

- The LADM, since it consists the first standard and approved base

model for the land administration domain (ISO 19152, 2012),

establishing a rigorous mechanism for managing legal RRRs, their

spatial dimension and the stakeholders. The implementation of this

standard to the marine domain seems feasible since the triplet

Object – Right – Subject, which consists the basis of LADM, applies

as well in the marine environment.

- The S-100 Universal Hydrographic Data Model, which provides the

framework and the appropriate tools to develop and maintain

hydrographic related data, products and registers. Following the

proposal made by Geoscience Australia in 2013 for the development of

a product specification for Maritime Limits and Boundaries, Canadian

Hydrographic Service & Geoscience Australia presented a model in

relation to LADM and marine environment. The report proposes the

extension of S-100 to support LADM, through the development of the

S-121 Maritime Limits and Boundaries (Canadian Hydrographic Service

& Geoscience Australia, 2016).

In order to develop and implement the aforementioned models into the

marine environment, the unique features of the marine space must be

taken into account. This paper explores the range of laws that dictate

marine interests, identifies the marine legal object and provides the

legislative framework and the RRRs that relate to marine space, in order

to be optimally organized towards the development of a MAS based on

international standards.

2. INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS RELATING TO MARINE ENVIRONMENT

Standards are widely used, since they provide efficiency and support

in communication between organizations and countries as well as for

system development and data exchange based on common terminology. Domain

specific standardization is needed to capture the semantics of marine

administration. Such a standard will support marine registry and

cadastral organizations utilizing a Geographic Information System along

with a Data Base Management System and applications, in order to

implement and support marine policy measures.

Current discussions and efforts focus on the development and

implementation of marine data modeling taking into account practices

from Land Administration Standardization. Therefore, the registration of

interests encountered in the marine environment with their spatial

dimension may be modeled in accordance with terrestrial mapping methods

and standardization techniques (Canadian Hydrographic Service &

Geoscience Australia, 2016). The basis of the model will be the S-100 –

IHO Hydrographic Geospatial Standard for Marine Data and Information.

2.1 LADM

The LADM, was approved on the 1st of November 2012 as an

international standard, ISO 19152, constituting the first adopted

international standard in the land administration domain. LADM provides

a formal language for the description of existing systems, based on

their similarities and differences. It is a descriptive standard, not a

prescriptive one that can be expanded. LADM is organized into three

packages and a subpackage (Lemmen, 2012). These are groups of classes

with a certain level of cohesion. The three packages are: Party Package;

Administrative Package; Spatial Unit Package and subpackage: Surveying

and Spatial Representation Subpackage. The model contains thematic and

spatial attributes. Furthermore in several attributes code lists are

used rather than character strings in order to ensure consistency. The

modification and adoption of code lists in national profiles is

possible.

From the 3D perspective, LADM supports both 2D

(LA_BoundaryFaceString) and 3D objects (LA_BoundaryFace) and

distinguishes legal and physical objects by introducing external classes

for BuildingUnit and UtilityNetwork. It covers the legal space while the

physical counterparts are not directly generated in LADM. At the

semantic level, legal entities are not enriched by classifying data in

relation to each other (Aien et al, 2013). Furthermore, LADM through the

VersionedObject class provides the attributes beginLifespanVersion and

endLifespanVersion, allowing the recreation of a dataset at a previous

point in time leading to a 4D visualization of the Cadastre

(Griffith-Charles and Sutherland, 2014).

The implementation of the model in marine environment is a user

requirements in LADM version A. Furthermore the scope of the standard

explicitly addresses the water when referring to land. Lemmen (2012)

states “With some imagination the laws (formal or informal) can be seen

as ‘parties’; in fact the laws allow people to have interests in ‘marine

objects’. The interests are RRRs”. The common denominator or the pattern

that can be observed in land administration systems as it is derived

from the LADM is with a package of party/person/organisation data and

RRR/legal/administrative data, spatial unit (parcel) data. The same

pattern is also applicable on marine space.

2.2 S-100 Universal Hydrographic Model

S-100 provides a contemporary hydrographic geospatial data standard

that can support a wide variety of hydrographic-related digital data

sources. It is fully aligned with mainstream international geospatial

standards, in particular the ISO 19100 series of geographic standards,

thereby enabling the easier integration of hydrographic data and

applications into geospatial solutions.

The primary goal for S-100 is to support a greater variety of

hydrographic-related digital data sources, products, and customers. This

includes the use of imagery and gridded data, enhanced metadata

specifications, unlimited encoding formats and a more flexible

maintenance regime. This enables the development of new applications

that go beyond the scope of traditional hydrography - for example,

high-density bathymetry, seafloor classification, marine GIS, et cetera.

S-100 is designed to be extensible and future requirements such as 3-D,

time-varying data (x, y, z, and time) and Web-based services for 85

Katerina Athanasiou, Efi Dimopoulou, Christos Kastrisios and Lysandros

Tsoulos Management of Marine Rights, Restrictions and Responsibilities

according to International Standards 5th International FIG 3D Cadastre

Workshop 18-20 October 2016, Athens, Greece acquiring, processing,

analysing, accessing, and presenting hydrographic data can be easily

added when required (IHO,2015).

Following the adoption of S-100, many product specifications are

under development by the IHO S-100 specialized Working Groups (WGs)

including S-101 for Electronic Navigational Charts (ENCs) and S-121 for

Maritime Limits and Boundaries.

The proposed S-121 is built upon the ISO 19152, which provides a

rigorous mechanism for handling legal RRRs. The intended purpose of

S-121 is “to provide a suitable format for the exchange of digital

vector data pertaining to maritime boundaries” and “for lodging digital

maritime boundary information with the United Nations for purposes

related to UNCLOS” (McGregor, 2013) What is more, as all ISO 19000

series product specifications, S-100 and the subordinate S-121 are

intended to interwork with all similar products. In that sense, S-121

may serve as the bridge between the land and marine domains while the

Maritime Limits and Boundaries following the S-121 standard may be used

in a MAS.

In S-121 each real world feature is an object with properties

represented as attributes (spatial and thematic) and associations which

establish context for the feature. The spatial attributes of the feature

describe its geometric representation, whereas the thematic attributes

describe its nature. The attributes associated with the geographic

feature depend on the intrinsic type of the feature, a concept derived

from LADM which is not included in the S-100 suite. A feature object may

only have one intrinsic type that is the physical dimension of the

feature in the real world based on the “Truth on the ground” principle.

Hence a feature may either be a point (Location), curve (Limit), area

(Zone) or volume (Space). Subsequently, the feature is described in the

dataset by the geometry property (point, line, area) which is used for

its cartographic representation. Finally, for the portrayal of each

geometry property, which is separate from geometric representation, a

variety of symbols may be used. For instance, the intrinsic type of a

football field is Zone. Depending on the scale of the cartographic

product, the geometry of the field may be area (large scale maps) or

point (small scale maps). Finally, for the portrayal of e.g. the point

geometry, can be used a simple point, a star or a variety of other

symbols.

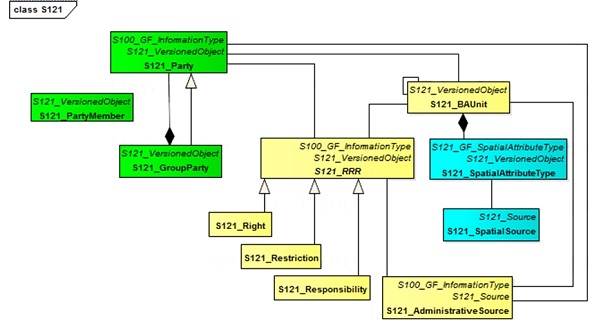

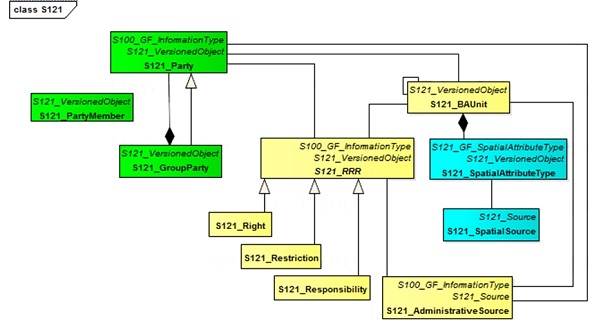

Figure 1. S-121 classes related to LADM

The proposed S-121 is a product based on S-100 which has many

similarities to the LADM, as it imports from LADM primitives not

supported by S-100, but differences as well. In example, GM_Curve and

GM_Surface from the ISO 19152 class LA_SpatialUnit are useful for a MLB

standard and therefore have been imported to the S-121. A fundamental

difference between the LADM and the S-121 is the use of the

Multi-primitive MultiSurface features in the land environment, whereas

in the marine environment it is a requirement from S-100 to use complex

features instead. In detail, when an object is crossed by another, in

land the crossed feature is defined as a multi-surface, whereas in the

marine environment each spatial primitive is a simple rather than a

complex one. Another issue is the use of 3D objects which LADM addresses

with the LA_BoundaryFace and LA_BoundaryString, whereas, due to the

limitations of S-100 which does not address 3D objects, S-121 handles 3D

objects as 2D objects with vertical extent (2.5 dimensions) (Canadian

Hydrographic Service & Geoscience Australia, 2016).

2.3 INSPIRE

For cross-border access of geo-data, a European metadata profile

based on ISO standards is under development using rules of the

implementation defined by the Infrastructure for Spatial Information in

the European Community – INSPIRE (ISO 19152, 2012). INSPIRE (Directive

2007/2/EC) focuses strongly on environmental issues, while the LADM has

a multipurpose character. One important difference is that INSPIRE does

not include RRRs in the definition of cadastral parcels.

From the spatial perspective, according to ISO 19152 (2012) there is

a compatibility between LADM and INSPIRE. More specifically, four

classes are relevant in the INSPIRE context:

- LA_SpatialUnit (with LA_Parcel as alias) as basis for

CadastralParcel;

- LA_BAUnit as basis for BasicPropertyUnit;

- LA_BoundaryFaceString as basis for CadastralBoundary;

- LA_SpatialUnitGroup as basis for CadastralZoning. Regarding the

marine space, the expression and the definition of the above classes

needs to be examined.

INSPIRE data specifications are being developed across 34 themes. A

number of INSPIRE themes have a marine relevance, something that

researchers have already pointed out (e.g. Longhorn, 2012). Two of the

themes, i.e. Ocean Geographic Features (OF) and Sea Regions (SR) are

related exclusively to marine environment. According to Millard (2007),

”INSPIRE is not marine nor land centric”. Themes are considered

independent of whether or not refer on land or at sea, and therefore

data can be brought together across land-sea boundaries. INSPIRE

provides a level of interoperability to deliver integrated land-sea

datasets. But the data models (by design) will not solve the needs of

all communities e.g. navigation. The marine themes on their own do not

give all the information on the marine environment. According to Lemmen

(2012) “firstly, it is possible that a European country may be compliant

both with INSPIRE and with LADM and secondly, it is made possible

through the use of LADM to extend INSPIRE specifications in future, if

there are requirements and consensus to do so”. Given that IHO S-121

”Product Specification for Maritime Limits and Boundaries” is based on

LADM, it is inferred that INSPIRE can cooperate as well with S-121

mainly in the spatial dimension.

3. LEGAL FRAMEWORK OF THE MARINE ENVIRONMENT

When considering the legal framework for the marine environment,

certain factors must be taken into account: the laws that define the

interests, the hierarchical classification of these laws considered as

reasonable (Cockburn and Nichols, 2002), how should this classification

be used to derive the principles for the implementation of MSP and how

the registration of laws in a MAS can automatically define the

constraints of the emerging RRRs.

Given the particular nature of the legal system of the marine space

and the necessity of an organized setting for its use, based on already

predetermined planning, the rights that may appear are defined in a

unique way by the law. Unlike land, maritime space does not allow the

rights’ creation as a private enterprise product and seeks for a

regulation with a direct correlation to the creation of the right and

the need to impose its creation. The term "law" refers to the wider

legislative framework which is the basis of MAS. Laws and regulations

create or describe rights and then provide the means to implement or

enforce them. Thus, in order to develop a MAS, the registration of laws

is considered reasonable. This section presents both the institutional

framework that defines the legal status of the marine space and the

legal framework that defines the application of these laws.

The international law defines the kinds of RRRs that may exist within

the marine space, which falls under the sovereignty of a state. A

considerable part of international law is consent-based governance. This

means that, with the exception of those parts that constitute customary

law, a state is not obliged to abide by this type of international law,

unless it has expressly consented to a particular course of conduct.

This is an issue of state sovereignty. Treaties may require national law

to conform to respective parts and they are commonly transposed into

national legislation by typical law.

The European Union Law (mainly the EU Directives) aims to establish a

common framework and a common approach for the development of an

Integrated Maritime Policy. Memberstates should implement the EU

Directives transposing them into national law. The choice of appropriate

form and method to implement relies at their discretion (Article 288,

Treaty of Functioning of the European Union). For example in Greece, an

EU Directive is commonly incorporated into the national legislation by a

typical law.

3.1 International level

Although domestic law is playing an important role in regulating the

management of the sovereign areas of a State, in the marine environment

international law has been the primary basis for the implementation of

maritime policies and boundaries.

Historically, the world’s oceans operate under the principle of

freedom of the seas. The multitude of claims, counterclaims, sovereignty

disputes between the States with coastlines, the rapid improvement in

technology and the increasing interest in exploring the marine

environment has caused the need for an effective international regime

governing the world’s oceans. The most intensive efforts have taken

place at the 20th century. In 1982 the UN concluded to the UNCLOS, which

forms the cornerstone of the legal mechanism and describes the rights,

obligations and types of interests of states.

One of the ways established has been through the division of marine

space into different zones where the coastal states enjoy sovereignty or

sovereign rights and thus the jurisdiction to establish their laws and

policies, in compliance with UNCLOS guidelines. The exercise of these

rights is subject to a registration system of Management of the marine

area. According to Cockburn et al (2003), UNCLOS influences a ratified

nation’s MAS in several ways, like breadth, depth, what rights can be

included in the ocean areas and hence what spatial information is

contained therein and has an effect on the evidence that can be used for

boundary delimitation. UNCLOS has created a complex three-dimensional

mosaic of private and public rights (Ng’ang’a et al, 2004), which the

party members have to incorporate into their national legislation, with

the enactment of new and/or modernization of national laws and

regulations.

The Convention is the background of exercising any marine activity

and therefore the reason to create a MAS, since it creates a sovereignty

status on the marine space.

3.2 European level

The main EU legal instruments that refer to the integrated management

of the Mediterranean marine space, which e.g. Greece has been called/is

called to follow, without having incorporated all of them into its

national law, are the following:

The integrated marine management term dates back to 2006, in Green Paper

Need for a link among diverse EU policies affecting the marine

environment. Since then (De Latte, 2016):

- COM (2007)575 - Communication of 10 October 2007 - Integrated

Maritime Policy for the European Union (Blue Book)

- Directive 2008/56/EC of 17 June 2008 establishing a framework

for community action in the field of marine environmental policy –

Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD)

- MARINE KNOWLEDGE 2020:

- BLUE GROWTH / BLUE ECONOMY:

- accompanying Communication COM(2014)254 of 8 May 2014 –

Innovation in the Blue Economy

- Directive 2014/89/EU of 23 July 2014 establishing a

framework for maritime spatial planning (EU Official Journal of 28

August 2014)

- Directive 2007/2/EC of 14 March 2007 establishing an

infrastructure for spatial information in the European Community –

INSPIRE directive.

- After that the INSPIRE Marine Pilot Project has been launched to

help stakeholders of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive

2008/56/EC to understand how the obligations of the INSPIRE

Directive 2007/2/EC relate to the data and information management

aspects of the MSFD.

The European Maritime Policy is still under development. The most

recent activity on the MC in European Union is the agreement on the need

for a common study on the importance of MC to the European economy.

3.3 National level

As a result of the structure of international law it is estimated

that around 50% of the world’s oceans fall within the national

jurisdiction of coastal states, whereas the remaining 50% represent part

of the Area (Prescott and Schofield, 2005). Greece is a state virtually

surrounded by sea located in the central part of the Mediterranean sea.

In the western part of Greece lies the Ionian sea. The maritime front of

this part of the mainland and of the nearby islands generate rights of

continental shelf and EEZ (not yet declared) for Greece which overlap in

with the corresponding rights of Italy, Albania and Libya. In the East,

Greece shares maritime borders with Turkey and Cyprus. In the south of

Crete lies the Libyan /South Kritiko sea, which covers the area

bordering with the Cretan, the Libyan and the Egyptian coasts. Therefore

the maritime neighbors of Greece are Albania, Italy, Libya, Egypt,

Turkey and Cyprus.

Concerning the international law, Greece ratified the 1982 Convention

on 21 July 1995 (Law 2321/1995). Thereafter the maritime borders are

defined as follows:

- The breadth of Greece’s territorial sea was set at 6 nautical

miles (NM) from the natural coastline in 1936 in the Mediterranean

Sea basin (Law 230/1936 as amended by Presidential Decree 187/1973,

which constitutes the Greek Code of Public Maritime Law). It has

been declared that Greece reserves its right under international law

to establish a 12 NC territorial sea at a time deemed appropriate.

However, the limit of 10 NC in the national airspace was maintained

explicitly based on previous legislation (Decree of 6 September 1931

in conjunction with Law 5017/1931).

- Regarding the Continental Shelf the distance between the Greek

coasts and the coasts of her neighboring states are less than 400NM,

and therefore Greece needs to agree its limits with the above

states. So far, Greece has concluded agreements with Italy (1977)

and Albania (2009) based on the median line principle. It is noted

that Greece has not declared an EEZ.

With respect to the legal framework for the management of the marine

environment, national legislation and regulation inevitably reflect the

specific interests, concerns and structures of the State. The manner in

which international Treaty law becomes part of national domestic law (or

is transformed into domestic law) is different for each State. Greece

has ratified UNCLOS and has enacted a number of laws for the areas she

exercises sovereign rights. What characterizes the Greek coastal and

marine area is the non-unified national strategy and the attempt to

resolve the issues presented by creating piecemeal provisions. There is

no comprehensive strategy to deal with the fractured and incomplete sets

of data that are the legacy of the complex administrative and legal

structures. The introduction of the General Framework for Spatial

Planning and Sustainable Development and the Special Framework for the

coastal area and the islands are a great advantage for these problems to

be solved. The creation of specific legislation on the shore and the

foreshore is an important part of spatial, urban and environmental

planning for the coastal area.

4. MARITIME ZONES AND LIMITS

4.1 Legal regime UNCLOS

codifies different maritime zones a coastal state may claim. The

maritime zones are measured from the baselines which normally coincide

with the low-water line (normal baseline) as marked on large-scale

charts officially recognized by the coastal State but can be any

combination of normal, straight, archipelagic and bay-closing lines.

Each zone grants certain rights to the coastal State and carries certain

obligations to the foreign States and vessels. The general principle is

that the closer to the coast the greater the degree of rights for the

coastal State, which consequently curtails some or all of the freedoms

for the foreign States and vessels. In detail:

- Internal Waters (IW), which cover all water on the landward side

of the baselines. The internal waters are considered part of the

State’s territory and the coastal State exercises full sovereignty

over them (UNCLOS, Article 8), similar to that on the land

Sovereignty is applied over the air space, water column, seabed and

subsoil, and postulates that foreign vessels and states are deprived

of all of the high seas freedoms, with the exception of Article

8(2).

- Territorial Sea (TS), measured from the baseline seaward, the

breadth of which may not exceed 12NM. The coastal State’s

sovereignty is extended beyond its land territory and internal

waters in the territorial sea (Article 2), also extending in the air

space over the territorial sea as well as to its bed and subsoil.

Sovereignty postulates that foreign vessels and states are deprived

of all of the high seas freedoms, but within this zone foreign

vessels enjoy the right of innocent passage (Article 19).

- Contiguous Zone (CZ), a zone adjacent to the territorial sea

which may not extend beyond 24 NM from the baselines. In the

contiguous zone the coastal State has the jurisdiction to regulate

and put laws into in order to prevent and punish infringements of

its customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws committed within

its land territory or territorial sea (Article 33). Moreover, in

order to control traffic of archaeological and historical nature

found at sea, the coastal State may, in applying the above relating

to the contiguous zone, presume that their removal from the seabed

in the zone referred to in that article without its approval would

result in an infringement within its territory or territorial sea of

the abovementioned laws and regulations. Within contiguous zone the

coastal state has no further rights and the high seas freedoms

remain unaffected for the other states.

- Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), which is adjacent to the

territorial sea and may not extend beyond 200 NM from the baseline.

In the Exclusive Economic Zone the coastal state has exclusive

sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting,

conserving and managing the natural resources, both living or

non-living and the jurisdiction to establish artificial islands or

installations and to conduct scientific research. Coastal state is

responsible for the protection of marine environment. Foreign

vessels enjoy three of the six high seas freedoms, namely the

freedoms of navigation, the freedom of overflight and that of laying

submarine cables and pipelines (Article 87).

- Continental Shelf (CS) which is again adjacent to the TS

and extends to the outer limit of the continental margin, which is

and is formed through the combination of the geological parameters

stipulated in article 76 of the Convention UNCLOS. More

specifically, the continental shelf is delineated by combining the

following three lines:

- 91 Katerina Athanasiou, Efi Dimopoulou, Christos Kastrisios

and Lysandros Tsoulos Management of Marine Rights, Restrictions

and Responsibilities according to International Standards 5th

International FIG 3D Cadastre Workshop 18-20 October 2016,

Athens, Greece

- The distance-constrained line which cannot exceed the 350NM

from the baseline o The depth-constrained line which may not

extend beyond 100NM from the 2,500 meter isobath and

- The formula line extending 60NM from the foot of the

continental slope.

However, the said geological parameters apply to the delimitation of

the area beyond the 200NM, known as the Extended Continental Shelf, as

up to the 200NM limit the continental shelf is another distant

constraint maritime zone. The rights over the continental shelf are

exclusive and pertain to the exploration and exploitation of natural

resources of seabed and subsoil. Unlike EEZ, which has to be proclaimed

by the coastal State, the sovereign rights of the coastal State over the

continental shelf exist ipso facto and ab initio. In other words coastal

State’s rights over CS “do not depend on occupation, effective or

notional, or on any express proclamation and, therefore, can be

exercised at any time” (Article 77).

- High Seas are all parts of the sea that are not included in any

of the above maritime zones. Over High Seas, all freedoms are

retained for every state. Mention should be made of “The Area” which

comprises the sea-bed, ocean floor and subsoil below the high seas

with the exception of that which is part of the state’s continental

shelf (including the continental shelf which lies beyond 200NM from

the baselines). The Area with its resources is common heritage of

mankind and must be used for the benefit of all states. It is

pointed out that some states, instead of taking full advantage of

the rights (and the consequent responsibilities) of the contiguous

zone, have chosen to declare “Archeological Zone” for the control of

traffic of objects of an archaeological and historical nature found

at sea. The removal of such objects from the seabed in that zone

without approval result in an infringement within its territory or

territorial sea of the laws and regulations referred to in article

33. Likewise, instead of declaring EEZ, states have chosen to

declare “Fisheries Zone” for the regulation of fishing based on

their exclusive sovereign right foreseen by UNCLOS for exploring and

exploiting, conserving and managing the living resources up to the

limit of 200NM from the baselines. It is noted that the above two

zones are not described as separate maritime zones in UNCLOS.

4.2 Methods of delimitation

Coastal states may delimit their maritime zones unilaterally at the

maximum allowable breadth, or, when one state’s zones overlap with the

respective zones of a neighboring state, up to the median/equidistant

line between the coastlines of the coastal states. The dominant method

for the unilateral delineation of maritime zones to their maximum

allowable breadth has been that of the conventional line constructed as

the combination of the ‘envelope of arcs’ for the natural coastline and

the ‘replica line’ (or tracé parallèle) for straight baselines. To

implement the envelope of arcs from a point on the normal baseline, an

arc is drawn at a distance equal to the breadth of the maritime zone

(Boggs, 1930) and the, so called, envelope line is the locus of the

intersections of the farthest arcs. On the other hand, the replica line

is created with the transfer of the straight line segments seawards at a

distance equal to the zone’s breadth. The outer limit of the maritime

zone is formed by the combination of the two lines (Kastrisios, 2014).

With respect to the bilateral delineation of maritime limits, the

geographer must define the median line ‘every point of which is

equidistant from the nearest points on the two baselines’ (UNCLOS,

Article 15). More precisely, “median/ equidistant line is the method to

be followed when the territorial seas of two coastal states overlap

(UNCLOS, Article 12). The same principle was present in the 1958

Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone with respect

to the contiguous zone (TSC, 1958, Article 24) and in the 1958

Convention on the Continental Shelf with respect to the continental

shelf (CSC, 1958, Article 12). However, the 1982 Convention remained

silent with regards the CZ, whereas for the continental shelf and the

exclusive economic zone (the latter was introduced into international

law with the 1982 Convention) the principle of equity was adopted

(UNCLOS, Article 74)” (Kastrisios and Tsoulos, 2016b). Towards achieving

an equitable solution the median line serves as the reference for the

final delimitation. In detail, “for the delimitation of maritime zones

beyond the 12 mile zone, the states would first provisionally draw an

equidistant/median line and then consider whether there are

circumstances which must lead to an adjustment of that line’ (ICJ (Qatar

v. Bahrain), 2001.

Either unilaterally or bilaterally, outer limits may be constructed

graphically on paper charts, semi-automatically with one of the existing

GIS software (e.g. CARIS LOTS) or fully automatically with the most

recent developments in the field (Kastrisios and Tsoulos, 2016a;

Kastrisios and Tsoulos, 2016b).

5. MARINE LEGAL OBJECT

For the development of a MAS the association of legal attributes with

maritime limits and boundaries’ information or marine parcels is

necessary, in order to determine under whose authority or international

treaty a particular limit or boundary is defined, and the restrictions

around this specific marine parcel according to the legislation.

From an administrative modeling viewpoint where the focus is on

abstracting the real world as a principle, sea is not a legal entity

until an interest is attached to it. Therefore, the very close

relationship between each interest and its spatial dimension in the real

world should be identified and registered in information systems. These

elements form a unique entity, the marine legal object.

Cadastres deal with entities consisting of interests in land that

have three main components: spatial (spatial units), legal documents,

and parties (Aien et al, 2013). The same applies in the marine

environment.

5.1 Types of RRRs

The operation of a LAS is based on the relationships between parties

(stakeholders) and property units. Property is conceptualized as

consisting of the rights, objects, and subjects. Nichols (1992)

suggested that property with its emphasis on ‘rights’ is a subset of

land tenure, which is a much broader term with emphasis on RRRs. In the

marine environment, property describes the resource, individual/s with

an enforceable claim, and type of resource use claims (Ng’Ang’A, 2006).

Moreover, other than the State owned parcels in the territorial sea,

parcel 93 Katerina Athanasiou, Efi Dimopoulou, Christos Kastrisios and

Lysandros Tsoulos Management of Marine Rights, Restrictions and

Responsibilities according to International Standards 5th International

FIG 3D Cadastre Workshop 18-20 October 2016, Athens, Greece boundaries

are determined according to usage only (e.g. minerals, aquaculture) and

not as a property. There is not a market in ocean parcels where parcels

are subdivided and consolidated and sold off, nor is the system designed

to support this (Barry et al, 2003). Therefore in oceans a different

legal regime is shaped. The following types of RRRs can be found:

- State Interests

The state RRRs are defined through the international Treaties (and

bilateral agreements for states with maritime neighbors) and

transposed into national legislation with laws. When referring to

sovereign rights, we mean the power of the state and/or the

sovereign entity (as regards the marine space, the sovereign entity

is always the coastal state) to act as they deem appropriate for the

benefit of their citizens. The legal term of the aforementioned

power is "exclusivity of jurisdiction" that is according to the

international law the state has complete control of its affairs

within its territory, without being accountable for the means of

exercising this control. The extent or the kind of the sovereign

rights differentiate according to the specific zone of the marine

space we are referring to. The full sovereignty or the sovereign

rights of the coastal state means that, apart from the coastal

state, private entities (natural or legal persons) can exercise an

activity or use part of the marine space only by means of

transferring of a right from the State for a specific activity under

contract or licensing. This kind of rights are recorded by a MAS.

- Public Rights

Public rights refer mainly to the constitutional right of every

citizen of the state having an unlimited/ without obstacles access

statewide (terrestrial and marine space). These rights are not

secured for an individual interest but for a public interest. They

may be described as protecting the public interest in the use and

conservation of social resources.

- Environmental RRRs

We refer to provisions that relate to the protection and

conservation of water resources, places of preserved areas and

cultural heritage. These places are pre-determined by law and the

rights involved are of supreme importance and mandatory, in

comparison to the following functional interests (Athanasiou et al,

2015). These RRRs include among others the protection of

archaeological and historical objects found at sea, the protection

of Marine Protected Areas and the general MSP restrictions.

- Usage and Exploitation Rights

Progressively functional rights tend to acquire a private nature,

associated with individual stakeholders that coexist with the state

rights. In a wide sense, this term sets the limits of rights, which

involve mainly the different ways of use, management and

appropriation. In other words, in the marine environment the rights

are limited in terms of space, duration and most importantly the

extent, the content that refers only to the different kind of uses

and management. The stakeholders are not owners but only beneficial

“users”. (Athanasiou et al, 2015). When private property rights are

used as a basis of interpretation, these rights do not represent

full ownership let alone absolute property rights; they can be

classified into usage and exploitation rights. Usage rights are

associated only with space, and exploitation rights are associated

with the resources as well. Usage rights may be granted by a legal

person that has been delegated the authority to provide usage

rights. Rights granted in this manner are subject to 94 Katerina

Athanasiou, Efi Dimopoulou, Christos Kastrisios and Lysandros

Tsoulos Management of Marine Rights, Restrictions and

Responsibilities according to International Standards 5th

International FIG 3D Cadastre Workshop 18-20 October 2016, Athens,

Greece restrictions in terms of the nature of the usage rights (e.g.

type and temporal aspects of use) and the spatial extent linked to

the usage rights (sometimes defined by boundaries). Functional

rights are granted either by leasing contracts or through licensing.

It has to be noted that the authority of granting remains national

and no freehold ownership is involved. These rights are associated

with specific stakeholders.

S-121 model maintains the class LA_RRR from LADM and the

specializations of LA_Right, LA_Restriction, LA_Responsibility, through

realization relationships. The class LA_Mortgage is not expressed in the

model, since there is not applicable in the marine environment.

5.2 Types of legal documents defining marine legal object

- Laws

The legislation which defines all RRRs of the marine space and is

the basis upon which the content of the administrative resources is

developed. The term "law" leads to the main division between

substantial and typical law (i.e. the legislation produced by the

legislative power of the House of Representatives). Thus, the

substantial law includes the principles of Common Law and equity,

the administrative acts of the Administrative Authorities

(Ministerial and Presidential Acts) as well as acts of legislative

content. Needless to say, the European Law (Treaties, Regulations,

Directives, Decisions) and the International law are main legal

binding sources.

- Administrative Sources

The legal sources which include the administrative regime of the

RRRs are defined. The administrative sources are: the legal

contracts that relate to the disposal of the functional rights of

the State to private entities (as defined by the legal framework).

The functional rights of the State granted are either by means of an

administrative contract (administrative long leases or public works

contracts) or the right is conferred by an administrative act, most

usually by a license agreement.

The administrative sources that need to be recorded in a MAS are

different depending on each activity. For several resources the

processes relating to registration of issue are standard. For example in

Greece the registration associated with exploration for and extraction

of gas and petroleum is highly refined. It is of high importance that

all the activities that take place in the marine space need to be

recorded accurately. This systematic recording could help to identify:

the multiple licenses required for specific activities, regulated access

rights, existing legal gaps.

S-121 model keeps the class LA_AdministrativeSource in its structure.

It is proposed the registration of administration sources and laws in

different classes. The fact that all different rights find their base in

some kind of transacting document is represented by the association

between S121_RRR and S121_AdministrativeSource and this transacting

document is recorded in the latter class. However in marine environment

the existence of rights may be not emerged through the transaction, but

from the law implementation.

5.3 Defining marine cadastral unit

A plethora of research works and papers in literature deal with the

definition of the marine parcel. Ng’ang’a et al (2004) make two

alternative hypotheses about the marine parcel: “(1) that there either

exists a multidimensional marine parcel that can be used as the basic

reference unit in a MC, or (2) that there exists a series of (special

purpose) marine parcels that can be used as basic reference units for

gathering, storing and disseminating information. In either case then,

whereas the definition and spatial extent of a parcel is still not

clarified, there still exists a parcel.”

Another definition of marine parcel refers to: “A confined space

having common specifications for its internal, mainly used as reference

to locate a phenomenon. A marine parcel facilitates the distinction

between contiguous territories and provides information concerning this

phenomenon through appropriate codification” (Arvanitis, 2013).

For the definition of the marine parcel certain issues must be taken

into account:

- The third dimension: The inherent volumetric 3D nature of marine

space is apparent. Marine RRRs, such as aquaculture, mining,

fishing, and mooring and even navigation, can coexist in the same

latitude and longitude but in different depths. The question is if

the 3D representation is necessary for a MAS. So far, the geomatics’

community supports the idea of the 3D registration and visualization

of marine interests. According to Ng’ang’a et al, 2004 “…Clearly,

the right to explore for minerals may have an impact on the surface

of the land, but it will also affect a 3D cross-section of the

parcel below the land’s surface. Policy-makers would no doubt

benefit from an understanding of the upper and lower bounds of the

exploration rights, and how these may affect the environment or

other property entitlements within the same parcel.” Additionally,

the registration of the restrictions that are defined by the laws

and structure the marine legal object are related with the third

dimension for most activities. They define in which vertical or

horizontal distance is allowed to exercise other marine interests.

Furthermore the multipurpose nature of the MAS demands access to

additional types of information (geology, hydrology etc.), except of

the RRRs, in relation to marine spatial extents. The use of the

third dimension is considered important. However the existing MAS

have only used the third dimension for the representation of the

seafloor.

- The fourth dimension: It is clear that time has always played an

important role as the fourth dimension in cadastral systems. In

marine environment most activities can coexist in time and space and

can move over time and space. Therefore the registration of the

fourth dimension will capture the temporary nature of many

particular rights.

- Spatial Identifiers: Every land parcel or property recorded in a

land registry or a cadastral information system must have an

identifier. In fact identifiers are the most important linking data

elements in land administration databases. There are various ways

for referencing land parcels and property. (Kalantari et al, 2008).

In the Hellenic (Land) Cadastre for each individual property a

12-digit code number is assigned, the “KAEK” , which is unique

nationwide. Arvanitis (2016) proposes the use of a unique code to

the marine parcels. “The 12-unit code will be based on the

legislated zone, the Sea, the Greek Prefecture, the Head Office of

the Port Authority Jurisdiction / Municipality, the use and number

of the marine parcel”. The code will be unique and will record the

existence of multiple uses in the third dimension. 96 Katerina

Athanasiou, Efi Dimopoulou, Christos Kastrisios and Lysandros

Tsoulos Management of Marine Rights, Restrictions and

Responsibilities according to International Standards 5th

International FIG 3D Cadastre Workshop

Athanasiou (2014) incorporates the elements of the unique code to the

spatial unit class in order to spatially define the MA_MarineParcel. The

attributes are: The unclosZone, with possible values - territorial sea

and EEZ, the physicalLayer, the seaType (in Greece for example, the sea

is divided in 8 different pelages) and the port authority – the values

of these attributes are from proposed code lists. Furthermore the

marineBlockCode is added, which is defined as “N°WGS84,

E°WGS84/codeOfSubdividedGrid“ (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Marine Parcel Package (Athanasiou, 2014)

5.4 Spatial dimension and associated issues

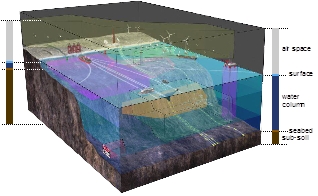

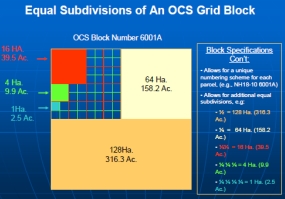

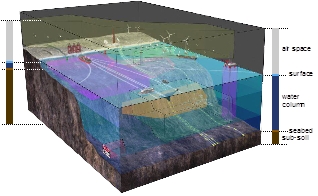

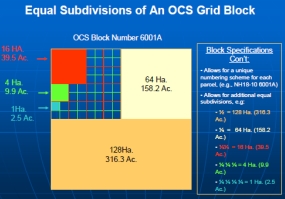

The basic reference unit, could be spatially defined as: a

multidimensional marine parcel or a series of (special purpose)

volumetric marine parcels (Ng’ang’a et al, 2004) or as sea surface

objects, water volume objects, seabed objects, and sub seabed objects

(Rahman et al, 2012) (Figure 3) or as a single piece of marine space

deriving from the determined and standard division of the maritime

surface using a grid of specific dimensions and subdivisions if needed

(Figure 4). It is specified by geodetic coordinates of the surrounding

boundaries. This method is already in use for defining the blocks in the

domain of minerals exploitation. The combination of these methods is

feasible. (Athanasiou et al, 2015)

|

Figure 3. 3D nature of marine parcel (NOAA, 2014)

|

Figure 4. Grid System for Oil and gas exploitation in USA

(BOEMRE, 2011)

|

The selection of the geodetic datum on which the coordinates will be

dreferred, is one of the issues that should be taken into account in the

development of a MC. A geodetic datum specifies the reference ellipsoid

and the point of origin from which the coordinates are derived.

Different states, even different mapping authorities of the same state,

use different geodetic datums.

Consequently, coordinates derived from one system do not agree with

the coordinates from another datum, with their differences between

adjacent states, as Beazley (1994) points out, amounting to several

hundred meters. In addition to the horizontal datums, the utilization of

different vertical datums has a significant impact as well. Hydrographic

Services, which are assigned with the task to map the marine

environment, as their priority is the safety of navigation they depict

depth soundings from a mean low water level, such as the Lowest

Astronomical Tide (LAT), or the more conservative Lowest Low Water

(LLW)". On the other hand, the Land cadastral services usually use the

Mean Sea Level (MSL). The difference between the two needs to be

precisely calculated. One of the factors affecting the calculation is

the distance of the permanent tide gauges from the location. The

different sea levels and the precise calculation of the sea level have

also a significant impact to the development of a MC. In detail, the

delineation of the coastline may vary greatly depending on the vertical

datum, which consequently has a significant impact to the outer limits

of the maritime zones over which the states exercise their rights. For

instance, as Leahy (2001) describes, for a foreshore of 0.5% gradient, a

difference of 0.5m in sea water level results 100m error in the location

of the coastline, a value that may exceed 200m in some cases. In extreme

cases and depending on the techniques followed for the delineation of

the coastline, Leahy calculated that the horizontal displacement of the

coastline may reach 3NM when (the coastline) has been derived from

topographic maps of scales 1:100.000.

And here comes another issue; where does the data come from? Is it

data acquired in situ using techniques according to specifications, or

data derived from paper charts/maps compiled years ago with obsolete and

error prone techniques? Another issue with the different sea levels is

the potential reclassification of a sub-surface feature to a low-tide

elevation, which may expand the maritime zones of the coastal state

[Article 13(1)].

We pointed out the importance of the precise delineation of the

baselines as they are the reference where from the maritime zones are

measured. However, it is not the only issue that affects the precise

division of marine space. As nicely put by Carrera (1999), “marine

boundaries are delimited, not demarcated, and generally there is no

physical evidence, only mathematical evidence left behind”, hence the

reference surface used for the delimitation of the outer limits and

boundaries is another source of error. While technical publications,

e.g. TALOS, state their preference towards the ellipsoidal earth,

something of the kind is not stated in UNCLOS. The maximum relative

error with approximating the earth as a sphere is 0.5%, but if projected

plane was to be used for creating buffers of the baselines (e.g.

Mercator projection) the produced error would be significantly greater.

Unfortunately, UNCLOS remains silent in many of its provisions

regarding the technical aspects of the delimitation, including the

horizontal and vertical datums, which the states need to consider and

agree with neighboring states towards an effective MC.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Recent research focuses on regulating the establishment of basic

principles, semantics, rules and procedures relating to the creation of

a MAS. So far, standardization is a requirement to support the

development of a National Land Information System. The same applies to

the marine environment, since the term land encompasses the water

element, as ISO 19152 states. S-100 gives the appropriate tools and

framework to develop and maintain hydrography related data, products and

registers. The extension of this standard to support the LADM, in order

to include the registration of additional types of marine data,

specified by the law is addressed through the development of S-121.

S-121 may serve as the bridge between the land and marine domains while

the Maritime Limits and Boundaries following the S-121 standard may be

used in the marine administration domain. Part of the S-121 project

development would be the specialization of the generic code lists of the

various attributes to marine environment for every State. Furthermore

given that IHO S-121 is based on LADM, it is inferred that INSPIRE can

cooperate as well with S-121 mainly in the spatial dimension. To this

purpose, the connection and the utilization of the terrestrial mapping

methods and standardization techniques must be examined.

Additionally, this paper refers to several issues that are related to

the definition of the marine legal object and need to be considered in

the development of a MAS.

- Organize national legislation, taking into account EU

orientations and directives. Government should enact appropriate

legislation and maintain a database referenced to a common spatial

system that is supported by appropriate standards. Furthermore, laws

and regulations that promote conflict in marine space need to be

identified with the resolution of spatial definitions within

legislation.

- The use of a unique code of identification for each marine

parcel is considered necessary for the establishment of a single

management system. The selection of the geodetic datum on which the

coordinates will be referred, is one of the major issues that should

be taken into account in the development of a MC, as well as the

level of accuracy in the delimitation of the marine legal objects.

- Regarding the Greek case, a conclusive approach becomes

progressively a matter of priority, which could support the State

and the European MSP initiatives. The delimitation of maritime

boundaries with its neighbors needs to be agreed upon, in order to

define the area where the MAS applies. In addition, the creation of

a national ocean’s policy would be the first step towards the

development of a MAS managing the complex regime of legislation and

overlapping jurisdictions.

REFERENCES

Aien, A., Kalantari, M., Rajabifard, A., Williamson, I. and Bennett,

R. (2013). Utilizing Data Modeling to Understand the Structure of 3D

Cadastres. Journal of Spatial Science. Issue 58 (2): pp. 215-234.

Arvanitis, A. (2013). Development of an Integrated Geographical

Information System for the Marine Space, Hellenic Cadastre, Athens.

Arvanitis, A., Giannakopoulou, S. and Parri, I. (2016). Marine

Cadastre to Support Marine Spatial Planning. In the Common Vision

Conference 2016 Migration to a Smart World, EULIS, Amsterdam, the

Netherlands.

Athanasiou, A. (2014). Marine Administration Model for Greece, based

on LADM. Bachelor Thesis, Department of Spatial Planning and Regional

Development, School of Rural and Surveying Engineering, National and

Technical University of Athens, Athens, Greece.

Athanasiou, A. Pispidikis I. and Dimopoulou, E. (2015). 3D Marine

Admininstration System, Based On LADM. In 3D Geoinfo Conference, Kuala

Lumpur, Malaysia.

Barry, M., Elema, I. and van der Molen, P. (2003). “Ocean Governance

in the Netherlands North Sea. New Professional Tasks”, Marine Cadastres

and Coastal Management, FIG Working Week 2003, Paris. France.

Beazley, P.B., (1994). Technical Aspects of Maritime Boundary

Delimitation, Volume 1 No. 2, International Research Unit, Durham

University, UK.

Boemre (2011). “Development of Marine Boundaries and Offshore

Leases”, Management of Marine Resources.

http://www.mcatoolkit.org/pdf/ISLMC_11/Marine_Boundaries_Offshore_Lease_Areas_

Management.pdf.

Boggs, S.W. (1930). Delimitation of the territorial sea: the method

of delimitation proposed by the delegation of the United States at the

Hague Conference for the Codification of International Law. American

Journal of International Law 24 (3), 5pp. 41-545.

Canadian Hydrographic Service & Geoscience Australia, (2016).

Supporting the ISO 19152 Land Administration Domain Model in a Marine

Environment, Paper for Consideration by HSSC & S-100 WG – Revised 26

February 2016.

Carrera, G. (1999). Lecture notes on Maritime Boundary Delimitation,

University of Durham, UK, July 12-15, 1999. Cockburn, S. and Nichols, S.

(2002). “Effects of the Law on the Marine Cadastre: Title,

Administration, Jurisdiction, and Canada’s Outer Limit”, In Proceedings

of the XXII FIG International Congress, 2002.

Cockburn, S., Nichols, S. and Monahan, D. (2003). UNCLOS’ Potential

Influence on a Marine Cadastre: Depth, Breadth, and Sovereign Rights. In

Proceedings of the Advisory Board on the Law of the Sea to the

International Hydrographic Organization (ABLOS) Conference "Addressing

Difficult Issues in UNCLOS". Presented at the International Hydrographic

Bureau, Monaco, October 2003.

CSC (1958). Convention on the Continental Shelf (Geneva, 29 April

1958) 499 U.N.T.S. 311; 15 U.S.T. 417; T.I.A.S. No. 5578 entered into

force 10 June 1964.

De Latte, G. (2015). MARINE CADASTRE General rights and charges under

the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) -

Patrimonial rights in the different marine zones - Registration of

patrimonial rights. 11 August 2015. de Latte, G. (2016). Marine Cadastre

– Legal Framework UNCLOS & EU legislation. In the Common Vision

Conference 2016 Migration to a Smart World, EULIS, Amsterdam, the

Netherlands.

Duncan, E.E. and Rahman, A. (2013). A Multipurpose Cadastral

Framework For Developing Countries-Concepts. Electronic Journal on

Information Systems in Developing Countries. Issue 58 (4): pp. 1-16.

Griffith-Charles, C. and Sutherland, M.D. (2014). Governance in 3D,

LADM Compliant Marine Cadastres. In 4th International Workshop on 3D

Cadastres, Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

ICJ (International Court of Justice), Maritime Delimitation and

Territorial Questions between Qatar and Bahrain (Qatar v Bahrain),

Merits, Judgment, 16 March 2001, ICJ Reports 2001, p. 40, para.212.

IHO (2015). Universal Hydrographic Data Model. Publication

S-100, ed. 2.0.0, June 2015, IHO, Monaco. ISO 19152 (2012).

ISO 19152:2012, Geographic Information – Land Administration Domain

Model. Edition 1, Geneva, Switzerland.

Kalantari, M., Rajabifard A., Wallace J. and Williamson I.

(2008).Spatially referenced legal property objects. Journal of Land Use

Policy. Issue 25 (2): pp. 173-181.

Kariotis, C.T. (1997). Greece and the Law of the Sea, Published by

Kluwer Law International, the Netherlands, 1997. Kastrisios, C., (2014).

Graphical Methods of Maritime Outer Limits Delimitation, Nausivios

Chora, Piraeus, 5/2014. (Available at

http://nausivios.snd.edu.gr/docs/2014E1.pdf).

Kastrisios, C. and Tsoulos, L. (2016a). An Integrated GIS Methodology

for the Determination and Delineation of Juridical Bays, Ocean & Coastal

Management, Volume 122, Pages 30–36.

doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.01.005.

Kastrisios, C. and Tsoulos, L. (2016b). A Cohesive Methodology for the

Delimitation of Maritime Zones and Boundaries, Ocean & Coastal

Management, Volume 130, Pages 188– 195.

doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.06.015.

Leahy, F.J., Murphy, B.A., Collier, P.A. and Mitchell, D.J. (2001).

‘Uncertainty Issues in the Geodetic Delimitation of maritime

Boundaries’, Proceedings of the International Conference on Accuracies

and Uncertainties Issues in Maritime Boundaries and Outer Limits,

International Hydrographic Bureau, Monaco.

Lemmen C.H.J (2012). “A Domain Model for Land Administration”, PhD

Thesis, Technical University of Delft, 2012.

Longhorn, R. (2012). Assessing the Impact of INSPIRE on Related EU

Marine Directives, In Hydro12 Conference, Rotterdam, 13 November 2012.

McGregor, M., (2013).., S-10X Maritime Boundary Product Specification

– Explanatory Notes. Paper presented at the 26th IHO Transfer Standard

Maintenance and Application Development Working Group (TSMAD) and 5th

Digital Information Portrayal Working Group (DIPWG), Silver Spring,

Maryland, USA, 10-14 June, 2013.

Millard, K. (2007). Inspire ‘Marine’ – Bringing Land and Sea

Together. HR Wallingford 2007. Ng'ang'a, S. (2006). “Extending Land

Management Approaches to Coastal and Oceans Management: A Framework for

Evaluating the Role of Tenure Information in Canadian Marine Protected

Areas”, Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering, University of

New Brunswick, 2006.

Ng'ang'a, S.M., Sutherland, M., Cockburn, S. and Nichols, S. (2004).

Toward a 3D marine Cadastre in support of good ocean governance: A

review of the technical framework requirements. Computers, Environment

and Urban Systems Journal. Issue 28: pp. 443-470.

Nichols, S. (1992). “Land Registration in an Information Management

Environment”. PhD Dissertation, Department of Surveying Engineering,

University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, NB, 340 pages.

Nichols, S., Ng’ang’a, S.M., Sutherland, M.D. and Cockburn, S.

(2006). Marine Cadastre Concept. Chapter 10 in Canada's Offshore:

Jurisdiction, Rights and Management. 3rd edition, Trafford Publishing,

Victoria, Canada. NOAA (2014). An Ocean of Information,

http://marinecadastre.gov.

Prescott, J.R.V. and Schofield C.H. (2005). The maritime political

boundaries of the world. Leiden: M. Nijhoff.

Rahman, A., van Oosterom, P., Hua, T.H., Sharkawi, K.H. and Duncan,

E.E. (2012). 3D Modelling for Multipurpose Cadastre. In 3rd

International Workshop on 3D Cadastres: Developments and Practices,

Shenzhen, China.

Rajabifard, A., Binns, A. and Williamson, I. (2005). “Administering

the Marine Environment. The Spatial Dimension”, Journal of Spatial

Science, 50(2): 69-78.

Rajabifard, A., Williamson, I. and Binns, A. (2006). “Marine

Administration Research activities within Asia and Pacific Region –

Towards a seamless land-sea interface”, FIG, Administering Marine

Spaces: International Issues, Publication No. 36, pp. 21 -36.

Strain, L., Rajabifard, A. and Williamson, I.P. (2006). “Spatial Data

Infrastructure and Marine Administration”, Marine Policy, 30: 431-441.

TSC (1958). Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone

(Geneva, 29 April 1958) 516 U.N.T.S. 205, 15 U.S.T. 1606, T.I.A.S. No.

5639, entered into force 10 Sept. 1964.

United Nations (1982). United Nations Convention on the Law of the

Sea, New York: United Nations, 1982. Widodo, M.S, (2003). The Needs for

Marine Cadastre and Supports of Spatial Data Infrastructures in Marine

Environment – A Case Study, FIG Working Week, Paris, France, April

13-17, 2003.

Widodo, M.S, (2004). Relationship of Marine Cadastre and Marine

Spatial Planning in Indonesia, 3rd FIG Regional Conference Jakarta,

Indonesia, October 3-7, 2004.

Widodo, S., Leach, J., and Williamson, I.P. (2002). Marine Cadastre

and Spatial Data Infrastructures in Marine Environment, Joint AURISA and

Institution of Surveyors Conference, Adelaide 25-30 November.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Katerina Athanasiou is currently a Master

Student of Geoinformatics at School of Rural and Surveying Engineering,

National Technical University of Athens. She graduated from the same

institution in 2014. Her bachelor thesis referred to the development of

a Marine Administration Model for Greece, based on International

Standards.

Efi Dimopoulou is Associate Professor at the School

of Rural and Surveying Engineering, NTUA, in the fields of Cadastre,

Spatial Information Management, Land Policy, 3D Cadastres and Cadastral

Modelling. She is the Programme Director of the NTUA Inter- Departmental

Postgraduate Course «Environment and Development» and President of the

Hellenic Society for Geographical Information Systems (HellasGIs).

Christos Kastrisios is Lieutenant Commander of the

Hellenic Navy and PhD candidate in Cartography at the National Technical

University of Athens (NTUA). After his graduation from the Hellenic

Naval Academy (HNA) in 2001 he served on board frigate and submarines of

the Hellenic Navy Fleet, until 2008 when he was appointed to the

Hellenic Navy Hydrographic Service (HNHS). His assignment at the HNHS

includes various posts including that of the deputy director of

Hydrography Division and his current position as the Head of the

Geospatial Policy and Foreign Affairs Office. He is the national

technical expert on the Law of the Sea, representative and member in

NATO and IHO working groups and member of national and international

geospatial societies. He holds a Master’s degree in GIS from the

University of Maryland at College Park. He is part-time lecturer at the

HNA and NTUA.

Lysandros Tsoulos is professor of Cartography at the

School of Surveying Engineering - National Technical University of

Athens [NTUA]. In 1975 he joined the Hellenic Navy Hydrographic Service

[HNHS] where he worked for 17 years (Directorate of Cartography and the

HNHS Computing Center). In 1992 he was elected member of the faculty at

the School of Surveying Engineering - NTUA. He is the director of the

NTUA Geomatics Center and the Cartography Laboratory. His research

interests include cartographic design, composition and generalization,

GIS, digital atlases, spatial data and map quality issues, spatial data

standards and the law of the sea. Currently he is president of the

Hellenic Cartographic Society and member of national and international

scientific committees.

CONTACTS

Katerina Athanasiou

National Technical University of Athens

School of Rural & Surveying Engineering

9, Iroon Polytechneiou

15780 Zografou

Athens

GREECE

Phone: +30 6948 879545

E-mail:

[email protected]

Efi Dimopoulou

National Technical University of Athens

School of Rural & Surveying Engineering

9, Iroon Polytechneiou

15780 Zografou

Athens

GREECE

Phone: +30 210 7722679

Fax: +30 210 7722677

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: http://www.survey.ntua.gr

Christos Kastrisios

Cartography Laboratory

Faculty of Rural and Surveying Engineering

National Technical University of Athens

9, Iroon Polytechneiou

15780 Zografou

Athens

GREECE

Phone: +30 6936 799258

E-mail: [email protected]

Lysandros Tsoulos

Faculty of Rural and Surveying Engineering/ Cartography Laboratory

National Technical University of Athens

9, Iroon Polytechneiou

15780 Zografou

Athens

GREECE

Phone: +30 210 7722730

Fax: +30 210 7722734

E-mail:

[email protected]

Website: http://www.survey.ntua.gr